Since 1788, Francis Douce kept a lively correspondence with the travel writer Richard Twiss (1747-1821). A typical letter from Twiss, as Douce explained to his friend George Cumberland years later, would be like ‘an omnibus on twenty or more subjects’, including chess, toys, mechanics, music, botany, entomology, prints, rare books, arithmetic and antiquities.

Mary Dawson Turner after George Henry Harlow, Portrait of Richard Twiss, 1814 (Hope Collection, The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

Twiss’s queries were often accompanied by entertaining comments and by explanatory sketches in pencil. His letters show how the exchange of objects and information contributed to his and to Douce’s research, as well as to the formation of their collections. Parcels containing books, prints, seeds and other ‘specimens’, as Twiss called them, were circulated regularly between his house in Bush Hill, Edmonton, and Douce’s address in Gower Street.

On 5 November 1793, Twiss wrote to Douce:

I wrote to you yesterday, I have just rec.d your favoured, & now return the book with thanks, & the caterpillars, they have done feeding, you must put them in a cup or jar with some very dry powder’d Earth, where they will make their nests.

Caterpillars seem to have been a subject of continued interest for both friends, since the following spring Twiss writes about them again:

I have some curious caterpillars &c why won’t you come & look at them? You might spare a Sunday. & then you shall see how we catch Butterflies by means of a squirt with water, shot above them while flying: this will do for all flying insects & does not injure them: it will also do for humming birds, but alas! we have none here.

Another caterpillar was delivered to Douce with detailed care instructions in September 1794:

The caterpillar (the large one I sent last) must have some soft moist Earth to make its pod in; if it is dead, I have two more; & likewise a fine cymps Rosa, & the sixlegg’d Greb of the stagbeetle which the plough has just turn’d up, but I suppose will die with cold tho’ I have put it in a box of Earth.

These caterpillars were not only properly fed and looked after, but also carefully observed and classified according to the Linnaean system. Twiss’s letters abound in bibliographical references to standard works, such as The Aurelian, or Natural History of English Insects, Snails, Moths, and Butterflies, together with the Plants on which they feed (London, 1766), whose author, Moses Harris, was the subject of a caricature in which the locks of his wig are replaced by curling caterpillars:

In Douce’s case, caterpillars also became the subject of some outlandish etymological speculations, which prompted Twiss to reply:

I do not like your Etymol. of Butterfly, because it is not true, neither that of chattepeleuse (which is also in Johnson). A caterpillar resembles a cat in being alive & having eyes, legs & guts, & that is all. We might as well compare a wasp to a wheelbarrow.

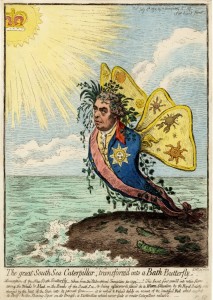

Douce’s interest in the systems of classification used by entomologists and botanists was not unusual among contemporary antiquaries, who often adopted a similar approach to the arrangement of their collections. Such exchanges were favoured by the close links between the Society of Antiquaries and the Royal Society, whose President (and Douce’s correspondent) Sir Joseph Banks was depicted as a caterpillar turned into butterfly in a satirical print by James Gillray, dated 1795:

James Gillray, The great South Sea caterpillar, transform'd into a Bath butterfly, 1795 (photo: The British Museum)