The quadrille-craze mentioned in my previous post on William Hawkes Smith’s music-sheet was also one of the subjects depicted by George and Isaac Robert Cruikshank in their illustrations to Pierce Egan’s Life in London (1821). In Egan’s social comedy, the quadrille appears associated with ‘Highest life in London’, as explained by the title of the plate showing ‘Tom & Jerry “sporting a toe”, among the Corinthians, at Almacks in the West’:

This publication was so popular that a theatre play ensued, and the two main characters became part of everyday language, as can be seen in this invective against modern life that Douce wrote in a letter to his friend George Cumberland, dated 30 October 1824:

Be assured, my dear sir, that nothing will alter the habits I have formed. It is not only too late in life, but I have a great aversion to modern life, or as that drole blackguard Egan called it in his humorous work, “Life in London” -Weston’s old housekeeper said to me the other day “Lord Sir, there are no people now that can talk on rational [matters] with you & my master, they are all Toms & Jerries” from whom I say “Good Lord deliver me”.

In a recent article, Sambudha Sen has discussed how Egan has recourse to ‘the discursive scheme of the urban high-low contrast’ to make his readers participant in low-life scenes and entertainments. The prints allow the reader seeing without being seen and ‘visiting’ East-End taverns, Covent Garden masquerades, and the Westminster pits without having to justify their presence there:

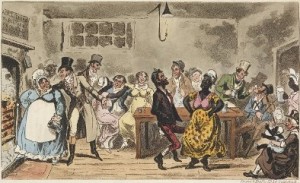

George and Isaac Robert Cruikshank, Lowest "life in London" - Tom, Jerry and Logic, among the unsophisticated sons and daughters of nature, at "All Max" in the East, 1821 (The British Museum)

Sen considers Egan’s work as pertaining to the same tradition as Hogarth’s ‘progresses’ and Dickens’s novels. By leafing through the plates, the reader may move up and down the social ladder without having to acknowledge any specific position within it -a detachment that has been linked both to ‘the snugness of the camera-obscura viewer’ and to the ‘externality’ of the flâneur (much better explained in Lauster, 2007).

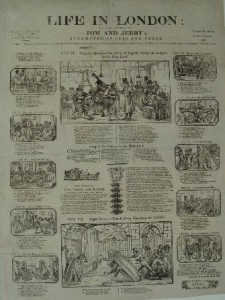

As David Kunzle notices, the great popularity of Egan’s publications was actually a ‘multimedia success’, not limited to the relatively expensive hand-coloured plates of Life in London: in 1822, the popular print publisher James Catnach produced this ‘twopence’ broadside, in which George Cruikshank’s scenes were copied (‘pirated’, according to Egan) and printed as woodcuts:

After George Cruikshank, Life in London; or, The Sprees of Tom and Jerry; attempted in cuts and verse, 1822 (The British Museum)

But what did Douce mean by ‘modern life’? Although he seemed to identify ‘modern’ with ‘urban’, in another paragraph from the same letter to Cumberland he elaborated on this subject: what he thoroughly disliked was, actually, the Industrial Revolution:

I hate gas lights, canals & steam boats altogether: you know the French hoax, viz. that they made brass parsons at Birmingham & caused them to preach by steam.