One of Douce’s most assiduous correspondents in the 1790s was the Shakespeare scholar George Steevens (1736-1800), of whom the DNB says that “his wit and the associated learning […] earned him the name of the Puck of Commentators”:

From his letters to Douce, it is clear that Steevens was a keen collector of prints and that their tastes and interests were rather similar. Douce and Steevens often exchanged not only information about works in their respective collections, but also prints, such as this ‘Exact copy of an ancient painting as large as the life, in Hungerfords Chapel at the East End of Salisbury Cathedral’:

Thomas Langley after J. Lyons, Copy of an ancient painting in Hungerfords Chapel, 1748, etching (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

Douce’s annotation on the margin explains that “The writing at bottom is Mr Steevens’s, to whom I am indebted for this print and the accompanying leaf of letter-press”, which has been pasted on the back of the mount:

Steevens sent the print as an example of “the manner of dressing and writing in England in the time of King Edward IV” -his own annotation shows that he was particularly interested in the cane “armed with spines” held by the young man in a leotard.

Douce, however, kept the print with his images of the Dance of Death. In 1833, he mentioned it as a depiction of “a portion of the Macaber Dance”, lost when the chapel was demolished in 1789-90. He added that “its destruction is extremely to be regretted, as, judging from that of the young gallant, the dresses of the time would be correctly exhibited” (The Dance of Death, London, 1833, pp. 52-53).

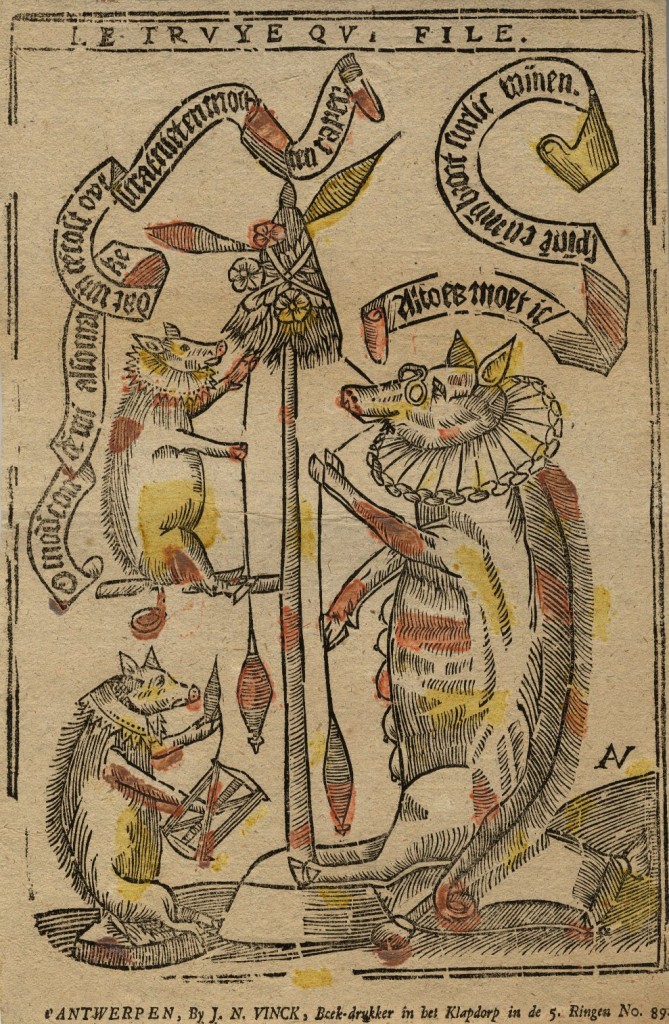

What else could be found in Steevens’s print collection? The catalogue of the sale, which took place in 1804 (Lugt 6819), shows a preference for portraits, 17thC and 18thC English prints, and Dutch and Flemish works. Lot 45 is described as “A Pair, from Breughel, Fat and Lean Kitchen”, framed and glazed. We know that Douce attended the sale because, in his Collecta, he wrote that he had “unaccountably missed” these two prints at the time. Nevertheless, he bought them “accidentally” a few months later when, acting on a tip from his friend Richard Twiss, he came across them again at a bookseller’s in Paddington Street:

Pieter van der Heyden after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Rich Kitchen, 1563, engraving (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

Douce had more than one impression of the print, but the annotation at the bottom confirms that this is the one formerly belonging to Steevens: “G.e S. Dono dedit / Henricus Blake Aren.r / talium formarum / Spectator amantissimus / 1766”.

The question remaining is: who was Henry Blake? In a footnote to his edition of Shakespeare’s plays, Steevens referred to “a gentleman to whom I have yet more considerable obligations in regard to Shakespeare. His extensive knowledge of history and manners, has frequently supplied me with apt and necessary illustrations […] I indulge my own vanity in affixing to this note, the name of my friend Henry Blake, esq.” (p. 48).