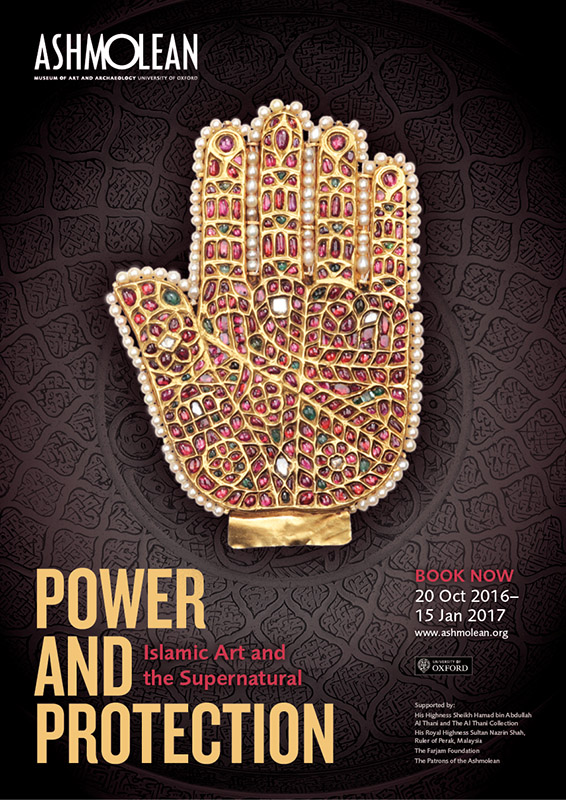

Exhibition dates: 20 October 2016 to 15 January 2017

Sainsbury Special Exhibition Galleries | Book tickets

The Ashmolean autumn exhibition, Power and Protection: Islamic Art and the Supernatural, is now open until 15 January 2017.

It looks at Islam’s attitudes towards the range of practices designed to predict one’s destinies and harness hidden forces for good luck and protection. The objects selected span from the 12th century to the present day, and were produced in a vast area stretching over three continents, from Morocco in the west to China in the east, and from Turkey in the north to Indonesia in the south.

Jar with Signs of the Zodiac

Iran, early 13th century, Fritware, painted in lustre over the glaze, Diam. 18.5 cm

Presented by Sir Alan Barlow, 1956. Ashmolean Museum (EA1956.58)

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

The exhibition is divided into three distinct but interconnected parts. The first gallery, titled ‘Interpreting Signs’, explores four types of divinatory techniques. It begins with astrology and its sister discipline astronomy, and looks at their interaction and integration with each other. Astrological imagery recurs on various types of objects, including the coffee set that once belonged to Fath ‘Ali Shah Qajar (r. 1797–1834) discussed in a previous blog post. The exhibition moves on to geomancy, or as known in the Arabic tradition, the ‘science of the sand’ (‘ilm al-raml). In this technique, the diviner traces 16 figures made of dots and lines on the sand and then interprets the sequence to answer a question. The next two divinatory techniques considered are dream interpretation and a practice known as bibliomancy, which uses books to foretell destinies and events.

Calligraphic Finial in the Shape of a Dragon

Golconda (India), late 17th–early 18th century, Brass, 18 x 10.7 cm

Purchased, 1994. Ashmolean Museum (EA1994.45)

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

The second gallery is titled ‘The Power of the Word’. It explores how objects carrying specific inscriptions (primarily sacred in nature) became imbued with protective, curative or talismanic powers. The Qur’an is the obvious primary resource of power and protection for Muslims, and examples of the Holy Book displayed in this gallery are opened on specific verses that are known to have been used for protective or healing purposes. The range of objects exhibited here, including arms and armour as well as the so-called magico-medicinal bowls, are inscribed with sacred words and thus appeal to their shielding or restorative properties.

Amulet

India, late 17th–early 18th century, Cornelian, inscribed and jade inlaid with gold and inset with emeralds and rubies, 3.2 x 4.1 cm

Presented by J. B. Elliott, 1859. Ashmolean Museum (EA2009.5)

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

The third and last gallery – ‘Amulets and Talismans’ – explores a wide selection of these objects. Many take the form of jewellery or small pocket-size objects, such as miniature Qur’ans or tiny scrolls kept inside cylindrical containers. Shops in various Muslim countries still offer devotional and preventive amulets for sale today. Also highlighted in this gallery are certain talismanic symbols which were considered blessed due to their associations with sacred individuals or sites. Among the most potent are the seal of Solomon and objects associated with the Prophet Muhammad, such as the mythical sword dhu’l-fiqar and his sandal (na‘l al-nabi). Finally, the exhibition looks at a selection of calligraphic works imbued with blessing (baraka) and protective powers, including the hilya (verbal portraits of the Prophet Muhammad) and calligrams (images made of words).

Pocket-size commodities and keyring sold at the Shrine of Eyüp, Istanbul

Private collection

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Further information on the themes and objects in the exhibition can be found in the exhibition catalogue and the exhibition microsite. There are also gallery tours as well as a series of talks and events on a range of topics relating to the exhibition, details of which can be found here.

For general information about the exhibition, click here.