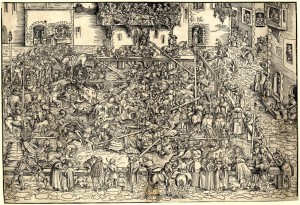

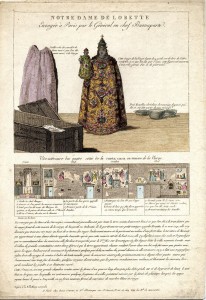

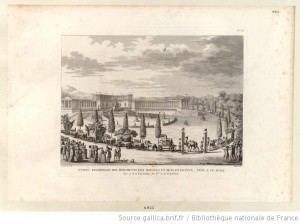

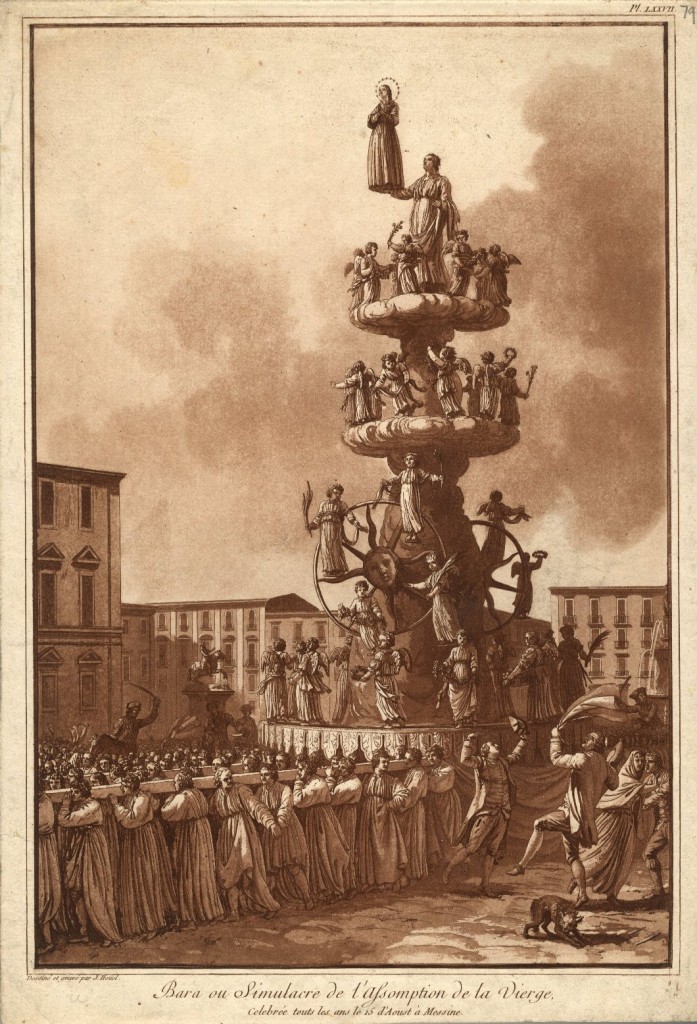

Between 1782 and 1787, the French painter and printmaker Jean Hoüel (1735-1813) published a travel book entitled Le Voyage pittoresque des isles de Sicile, de Malte et de Lipari. Douce included one of the 264 plates that illustrated Hoüel’s work among his prints of ‘Ceremonies’; according to the caption, plate 77 shows the religious festival known as ‘Bara, or Simulacrum of the Assumption of the Virgin, celebrated every year on the 15th of August in Messina’:

Jean Hoüel, Bara ou Simulacre de l'Assomption de la Vierge, c. 1779-82, aquatint (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

In the text accompanying the plate, Hoüel explained that he was so desirous of attending the festival that he worked day and night so that he could be free to travel to Messina. As a result, he became ill and when he arrived at 8 am on the day of the Assumption he was ‘almost dead’. Hoüel does not say whether the show was worth the inconvenience, but even in his dying state, he managed to provide a very detailed account of the celebrations and a precise description of the main contraption illustrated above:

Voyage pittoresque des Isles de Sicile, de Malte et de Lipari, vol.2

All the angels were actual children, and the Virgin was represented by a young girl of 14, who had to stand, rather precariously, on the hand of a sculpture of Christ. I was relieved to find out that, in the current version of the festival (called ‘Vara’ by the locals), the young girl and the children have been replaced with statues:

Hoüel assured his readers that the arrangements were perfectly safe and that neither the little children nor the girl could fall from the moving tower. The experience was, however, far from enjoyable for those most directly involved: in 1823, the Encyclopaedia Britannica quoted fragments from the Voyage pittoresque in their entry on the ‘Bara’, with the following addition:

This complication of superstitious whirligigs may have already nearly turned the stomachs of some of our readers, or at least rendered them squeamish. But think of the poor little cherubims, seraphims, and apostles, who are twirled about in this procession! for, says Mr Houel, some of them fall asleep, many of them vomit, and several do still worse: but these unseemly effusions are no drawback upon the edification of the people.