Long before subtitled Danish drama reached these shores*, Douce was already championing Scandinavian story-telling of a different sort, as transcribed by his friend the Danish scholar and antiquary Grímur Jónsson Thorkelin (1752-1829). On 28 April 1819, Douce wrote in his book of Coincidences:

A Col. Silverschildt a Dane called with a letter from my old friend Dr Thorkelin of Copenhagen at the moment when my nephew Tom was with me, who had probably exchanged shots with this Colonel at the infamous attack on Copenhagen.

John Bluck, View of Copenhagen ... during the bombardment ... 4th September 1807, 1808, hand-coloured acquatint (British Museum)

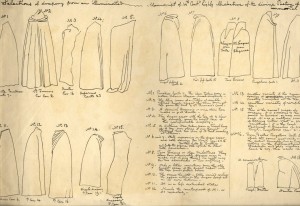

Among the many reasons Douce had to call the attack ‘infamous’, he probably counted the loss of the edition of Beowulf on which Thorkelin had been working for twenty years -his notes were destroyed when his house burnt down as a result of the British bombardment in 1807. Thorkelin’s edition was based on the extremely fragile manuscript now in the British Library, which he and James Matthews transcribed in 1786-7:

Fortunately, Thorkelin’s transcript of the poem survived the fire and, in 1815, he finally published the text under the title De Danorum rebus gestis secul. iii & iv, poëma danicum dialecto anglosaxonica. Douce owned copies of both Thorkelin’s edition (Bodleian shelfmark Douce SS 105 (101) and the English edition published by Kemble in 1833 -more details on transcripts, editions, and collations below:

University of Kentucky’s Electronic Beowulf

Douce might have been particularly interested in the sources of the poem and in the information on Scandinavian and Germanic mythology that it provided -this was part of its appeal to the ‘poetical antiquary’, as John Josias Conybeare remarked in his Illustrations of Anglo-Saxon Poetry (London, 1826), also on Douce’s book-shelves.

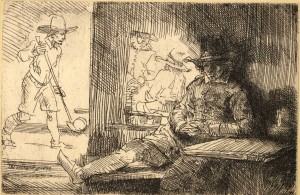

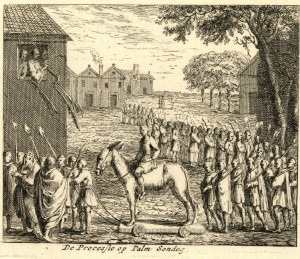

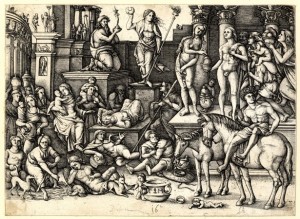

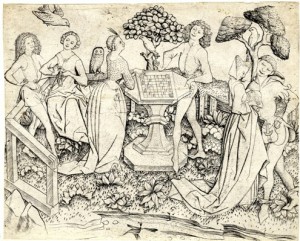

The customs and beliefs of ‘the Northern peoples’ were examined and illustrated in Olaus Magnus’ Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus (Rome, 1555), whose woodcuts are scattered among Douce’s prints of witchcraft. These images, which ended up integrated in the series of Douce’s prints arranged by subject, were probably cut from two different unidentified early editions of Magnus’ work. Douce owned at least three more copies of the book, including a first edition. They are all now in the Bodleian.

The woodcuts that I have seen so far are all from the third book of Magnus’ Historia, which deals with the ‘superstitious culture’ and pagan traditions of the North. Unusually for him, but very helpfully for later cataloguers, Douce annotated some of the images indicating the specific passage they illustrate, as can be seen in this depiction of a ‘Marine Magician’, practising his dark arts from what looks like a surf board:

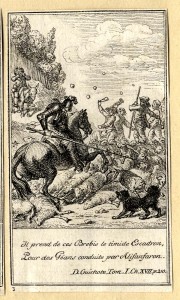

In the scene below, a swineherd and his pigs sit peacefully on top of a cliff totally oblivious to the incantation performed by a sorceress just behind them and to the shipwreck in the background. The first woodcut is the same illustration published in the first edition of Magnus’ book -the second is a later (and much more dramatic) copy:

* Danish drama wins global fanbase