At the moment, I am cataloguing Douce’s prints of games, sports, and popular pastimes. The reason why Douce collected these images can be found in the introduction to his friend Joseph Strutt’s The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England (London, 1801):

In order to form a just estimation of the character of any particular people, it is absolutely necessary to investigate the Sports and Pastimes more generally prevalent among them. War, policy, and other contingent circumstances, may effectually place men, at different times, in different points of view, but, when we follow them into their retirements, where no disguise is necessary, we are most likely to see them in their true state, and may best judge of their natural dispositions.

Most of the prints acquired by Douce are depictions of people playing games. Some, however, are actual game-boards, like this seventeenth-century etching used to play the Gioco del Gambaro (or ‘Game of the Prawn’) and published by Francesco de Paoli in Rome:

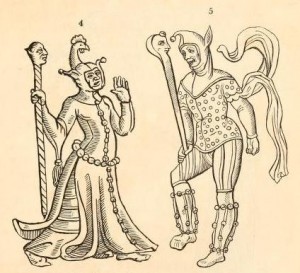

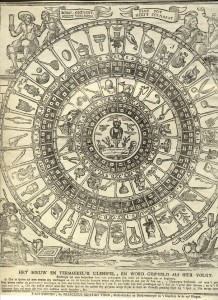

Many of these game-boards probably reproduce earlier designs, as can be seen in the Game of the Owl below. This woodcut was published in Antwerp in the second half of the eighteenth century, but the costumes worn by the figures drinking and laughing in the corners suggest that an older woodblock could have been used:

Similarly, the eighteenth-century Diletevole Gioco del’Ocha (Game of the Goose) below might be based on earlier models:

Similarly, the eighteenth-century Diletevole Gioco del’Ocha (Game of the Goose) below might be based on earlier models:

The British Museum owns a very similar woodcut from Lady Charlotte Schreiber’s collection (inv. no. 1893,0331.49). According to the annotation in black ink that can be seen in reverse at the bottom of the Ashmolean print, it belonged to Giuseppe Storck (1766-1836), a Milanese dealer and collector. Douce possibly acquired it through the dealer Samuel Woodburn, who bought many prints and drawings from Storck’s collection.

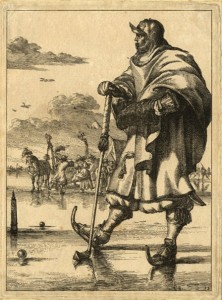

While Douce considered this print primarily as an example of Italian game-boards and he classified it as such, the location of Storck’s mark indicates that the latter valued it rather for the following image printed on the verso:

The female warrior on horseback is named in the inscription as ‘Marfisa Bizara’. This could allude to the title of the romance in verse by Giovan Battista Dragoncino da Fano, published in 1531. Alternatively, it could refer to the character in Lodovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso and have been printed as part of an unidentified series of celebrated women, like the ‘Marfisa Guerriera’ etched by Antonio Tempesta.

It is also possible, however, to identify the character depicted in the woodcut with yet another ‘Marfisa Bizzarra’: this was the title of a ‘facetious poem’ published by Carlo Gozzi in 1766. Gozzi’s work, in which the figure of the female warrior becomes an object of ridicule, has been included by Franco Fido in a study of what this author calls the ‘cultura del gioco’ (La serietà del gioco. Svaghi letterari e teatrali nel Settecento, Lucca, 1998). He refers specifically to the wit and playfulness that have long been associated with the eighteenth century when, as Robert Bufalini writes in his review of Fido’s book, ‘one finds the least distance between “culture” and “play”.