Exhibition dates: 21 Mar to 22 Oct 2017

Gallery 11 | Admission Free

Collecting the Past, Scholars’ taste in Chinese Art, on view at the Ashmolean Museum of Art & Archaeology, Gallery 11, March 21st through October 22nd, 2017, explores literati aesthetic taste and the tradition of collecting the past in Chinese art.

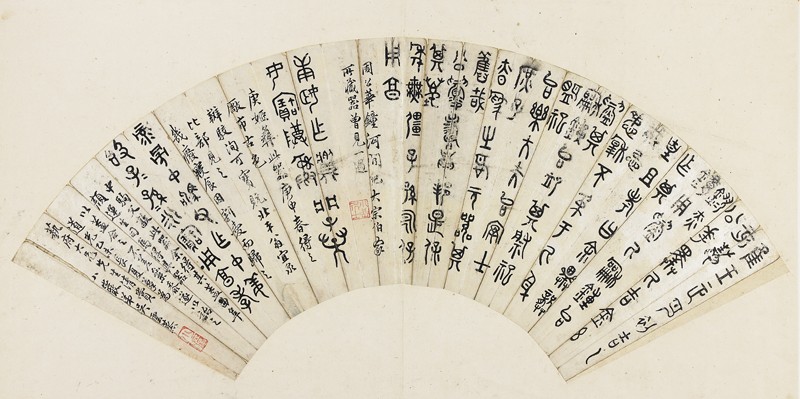

Wu Hufan, Calligraphy from Seeing Mr Lu Returning to Wu, ink and colour on paper, 39.9 x 62.6 cm, Reyes Gift 1995 © the Artist’s Estate, EA1995.290

Scholar artists as collectors

This exhibition also features calligraphy and paintings by some prominent scholar artists who were also celebrated collectors and art connoisseurs in the early 20th century. Wu Hufan (1894-1968) was a painter, calligrapher and connoisseur. He was the grandson of Wu Dacheng (1835-1902), a leading official at the Qing court and an amateur literati artist, who was also well-known as a celebrated collector of ancient bronzes, jades and rubbings. Wu Hufan inherited family collections of artworks, and began his artistic practice by copying old masters. The landscape album on display was painted in Wu’s studio, named Plum Vista Studio, which was the main art center for appreciating and exchanging ancient paintings and calligraphy in the Jiangnan area. Benefiting from his family collection and contact with other collectors, Wu Hufan was able to study and collect works by earlier masters. Wu epitomizes the Chinese scholarly tradition of combining collecting with creativity, acquiring works of art as a way of learning from the past. The landscape album and fan calligraphy give Wu Hufan the opportunity to display his many talents—as connoisseur, painter and calligrapher.

Wu Hufan, Magnificent View of Landscape, 1930 – 1968, ink and colour on paper, 23.5 x 29 cm, Reyes Gift 1995 © the Artist’s Estate, EA1995.254.a

The landscape album by the Guangdong painter Wu Hao (b.1930) is a direct copy of Shitao’s album of poetry and painting which was owned by Wu Hao’s friend, the collector Huang Yongyu (date of birth unknown), the Master of Heavenly Sound Pavilion. His grandfather and father are collectors and connoisseurs. Influenced by family, Wu Hao is a well-trained calligrapher, landscape painter, seal carver and poet. On the last page, the artist recorded the collecting history of Shitao’s album of poetry and painting. It used to belong to Kong Guangtao of the Snowy Mountain Pavilion (or Yuexuelou, the studio of Kong Guangtao) in the late Qing period. On each album leaf there is a connoisseur’s seal by Shao Tang. Also, Kong has invited Cantonese poets to compose poems for each leaf, showing how much he treasured this album. In winter 1933, when Zhang Yuan (Chang Dai-chien) came from Neijiang (in Sichuan province) to Guangzhou Huang Yongyu showed this album to him. Zhang highly praised this album, saying that the album features so many styles. In Zhang’s preface he wrote: ‘I have ten albums of Qingxiang (Shitao) in my own collection, and I have seen no less than 20 – 30 albums of his when I travelled North and South in this country, but none of those is as fantastic as this one.’ Zhang also signed the preface as ‘Daqian with extreme joy’.

Collecting the Past: Scholars’ Taste in Chinese Art, exhibition view of the albums by Wu Hufan (left) and Wu Hao (right)

Objects in the Scholar’s Studio

A well-equipped scholar’s studio was filled with fine furniture and tasteful objects, and artefacts of all sorts from archaeological objects to copies of antiques. The studio was a place of artistic expression and experimentation, and it was also a place of social gathering for literati elites, such as Wu Hufan’s Plum Vista Studio. For instance, the image of a group of objects in a scholar’s study portrays a typical day in a scholar’s studio: he opened all the windows, cleared his desk, burned incense, washed his hands and cleansed his ink-stone, and by doing so his spirit was calmed and his thoughts composed. This playful finger painting was created by the Sichuan artist Liu Xiling (1848 – 1923). His painting style and subject matter were inspired by Gao Qipei (1660-1734), a literati painter who was particularly well-known for his finger painting.

Liu Xiling, An inkstone, incense, and flowers, ink and colour on paper, finger painted, 31.4 x 36.5 cm © Ashmolean Museum, EAX.5345.d

For a scholar and painter, ink and paint palettes were utilitarian items which were needed to hold excess ink and colour. The four basic pieces of equipment they used are called “the Four Treasures of the Scholar’s Studio”: paper, brush, ink and ink stone. On display are a group of ink sticks made in the Hu Kaiwen ink workshop which was established in Huizhou (East of China) in the 18th century, and supplied special ink sticks for the imperial Qing family. Chinese ink is produced in stick form rather than liquid, allowing it to last for generations without drying out. To use the ink, the stick is ground against the surface of the ink stone and water is gradually dropped from a water dropper. Freshly mixed ink is used with a Chinese brush to produce the whole variety of textures seen in Chinese painting and calligraphy.

Collecting the Past: Scholars’ Taste in Chinese Art, exhibition view of vitrine case with water pot, jar, ink sticks, Ten Bamboo Manual and wrist rest.

A set of brush washers from the 18th century mimics the glaze of Song Dynasty (960-1279) Guan ware. In later periods, particularly in the Qing dynasty, collectors and scholar elites greatly admired these simple wares for their antiquity as well as their subtle colours. The two ceramic incense burners shown from the same period are modelled after ancient ritual bronze gui-tureen vessel.

Brush pot with figures in a landscape, China, 1720 – 1770, jade, 16.5 cm x 17.7 cm (d), Fraser gift 1967 © Ashmolean Museum, EA1967.139

As a stone of beauty and eternity, jade has always been highly prized in China, and embodied the noble spiritual world beyond physical beauty, which is associated with the qualities of an ideal gentleman: pure, constant and incorruptible. A fine example of craftsmanship is the big dark green jade brush pot carved with a scene of two scholars in a garden. The archaic jade water dropper shaped in the form of a winged beast and delicately carved is another delightful object which would sit on a scholar’s desk and contribute to creating an atmosphere of cultural refinement.

Collecting the Past: Scholars’ Taste in Chinese Art, exhibition view of vitrine case with incense burner, jade brush pot, brush washer and water dropper.

Pursuing the past in painting and calligraphy

No later than the Song Dynasty (960-1279), archaic bronzes and their inscriptions, the result of hundreds of years of epigraphic and stylistic study by literary scholars and artists, became inseparable. In addition to their connection with the past, rubbings were valued for their association with personal possession. Collectors and scholar elites created works of painting, calligraphy, and of composite rubbings as a means of displaying their wealth and status. Wu Yunzheng’s fan calligraphy written in archaic script is an excellent example of antiquarian taste. This calligraphy was originally mounted as one side of fan. It copies the rubbings of a variety of ancient ritual bronze vessels, including the bronze bell of Zhu Gonghua (c.5th century BC), the yi-vessel of Lady Geng (undated), and the gui-tureen vessel of Zhongjufu (c.8th century BC).

Wu Yunzheng, Calligraphy after inscription on three bronze vessels, 1835, ink on silver paper, 23.5 x 52.3 cm © Ashmolean Museum, EA1965.243

Wu Changshuo (1844 – 1927), a student of Ren Yi, was known as one of the major figures in the Shanghai School of artists. He received traditional education in poetry, calligraphy, and seal carving at an early age. The scroll Peonies in a bronze vessel was painted in 1903. The bronze vessel in this painting is a ding tripod ritual vessel of the mid-Zhou dynasty (c. 1050-256 BC), depicted together with its inscription. Bronzes were first collected in the Song dynasty (960-1279), mainly for the historical importance of their inscriptions. The practice was revived in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), and a new way of representing the vessels was developed. Chrysanthemum and plum blossoms were favorite subjects of Wu, particularly the latter. More than once, he called himself “plum’s confidant.” This type of painting is characterized as Bogu huahui (Antiques and Flowers) and became very popular in 19th century Shanghai among the scholar elite because of a fusion of auspicious symbols and the depiction of ancient Chinese artefacts.

Wu Changshuo, Peonies in a bronze vessel, 1903, ink and colour with ink and rubbing on paper, 133 x 66 cm, Impey Bequest © Ashmolean Museum, EA2007.103

Bird and Flower

Over the centuries, cymbidium orchids were favoured by scholar artists, who often painted the leaves and blossoms calligraphically. The cymbidium orchid, along with the bamboo, the chrysanthemum and the plum blossom are called The Four Gentlemen in Chinese art. The handscroll Epidendrum, bamboo, and rocks by late Qing painter Gai Qi (1774 – 1829) begins in springtime, with clumps of orchids sprouting from rocky outcroppings. The brushwork highlights the profusion of leaves and blossoms. The fragile beauty of the cymbidium orchids is graceful in form. Such characteristics made it a natural symbol of refinement, elegance, virtue and moral excellence. (EA1962.225)

Collecting the Past: Scholars’ Taste in Chinese Art, exhibition view of Gai Qi, Epidendrum, bamboo, and rocks, 1818 (painting), 1877 (colophon), ink on paper, 30.48 x 351.79 cm © Ashmolean Museum, EA1962.225

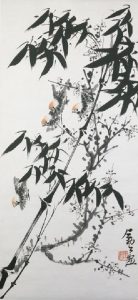

Among the Four Noble Plants, bamboo was particularly favoured by literati elites. In one of his poems, the Song dynasty scholar Su Shi (1037-1101) wrote: “I can go without meat in my meal, yet I can’t live in a place without bamboo.” Li Kuchan’s (1898 – 1983) painting Birds and bamboo especially emphasis the flexibility and strength of the bamboo stalk representing for literati painters the human values of cultivation and integrity.

Li Kuchan, Birds and bamboo, 1898 – 1965, ink and colour on paper, 96.52 x 45.72 cm © the Artist, EA1965.249

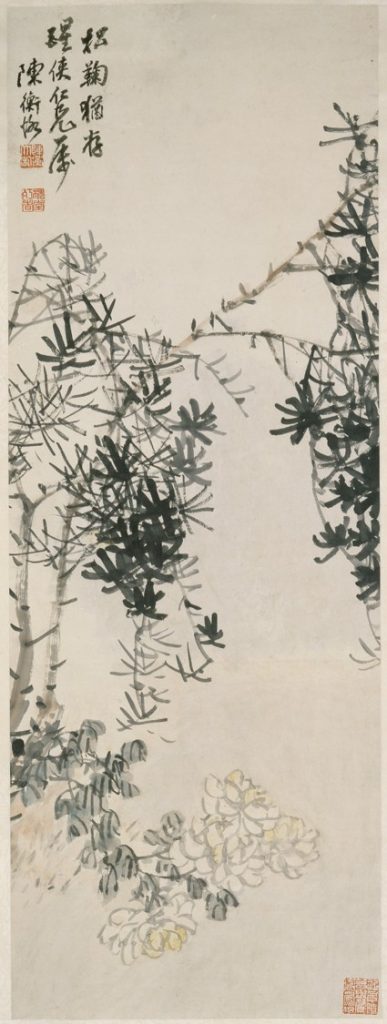

Chen Hengke’s (1876 – 1923) The Pine and the Chrysanthemum Endure focuses on the image of the pine and chrysanthemum and their ability to thrive even in the harshness of winter. They embody steadfastness, perseverance and resilience. Representing the ideal characteristics of a scholar-gentleman, these symbols of virtue became a popular theme in Chinese literati painting, poetry, and calligraphy throughout the ages.

Chen Hengke, The Pine and the Chrysanthemum Endure, 1901 – 1925, ink and slight colour on paper, 101.6 x 38.1 cm © Ashmolean Museum, EA1969.63

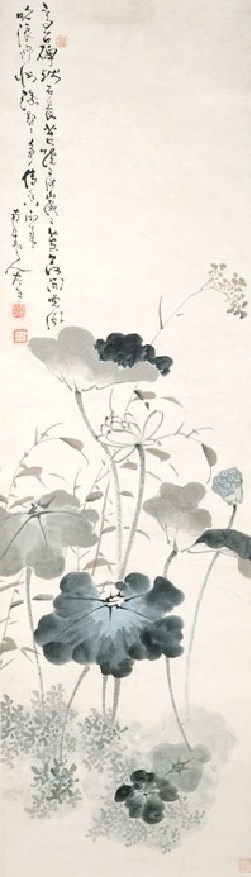

In Buddhism the lotus is known to be associated with purity and rebirth, it is also a favourite subject in Chinese ink paintings. Zhu Da (c.1626 – 1705), also known as Bada Shanren, was a descendant of the prince of Yiyang of the Ming imperial family. The use of the name “Bada Shanren” in 1684 marked a profound shift in his career from Buddhist monk to artist, and his painting style becomes more mature and expressive. Lotus dominated his visual vocabulary throughout his life.

ollecting the Past: Scholars’ Taste in Chinese Art, exhibition view with scrolls by Su Liupeng (EA2007.207) and Zhu Da (EA1965.66), Fu Baoshi (EA1963.71) and Li Kuchan (EA1965.249).

Gao Fenghan (1683-1749) was born in Jiaozhou, Shandong province, and spent his career as an official in the Jiangnan region, where he associated with the Yangzhou painters known later on as the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou for rejecting orthodox painting tradition. He painted this lotus scroll with very playful brushwork using his left hand when suffered from rheumatism in his right.

Gao Fenghan, Lotus, 1737 – 1741, ink and colour on paper, 154.94 x 45.72 cm © Ashmolean Museum, EA1965.253

Yan Liu, Christensen Fellow in Chinese Painting.