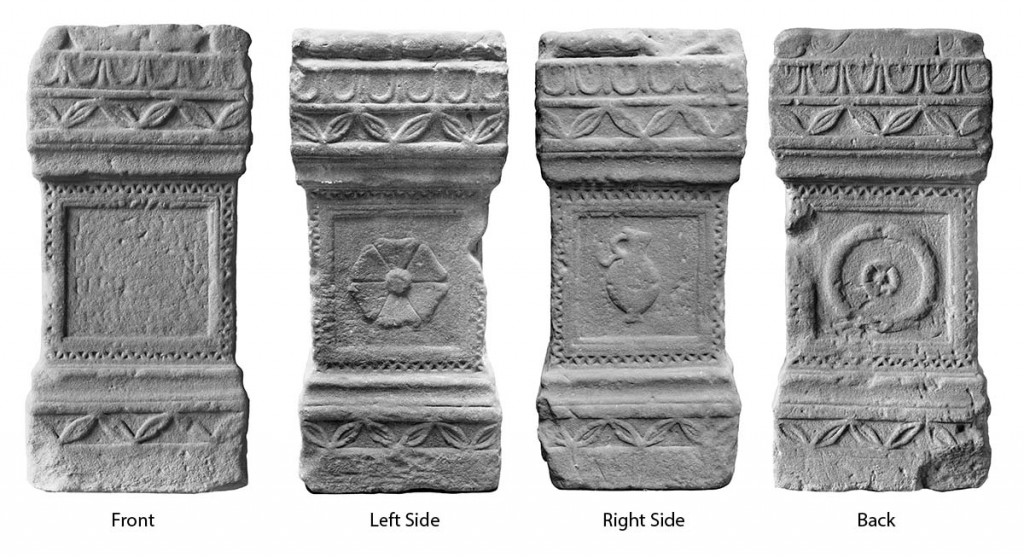

Ashmolean ANChandler3.1. Red Sandstone Altar from Chester (H. 0.97, W. 0.45, D. 0.43). AD 154.

On display in the Ashmolean’s Ark to Ashmolean gallery stands a red sandstone altar. On three of its sides there are relief designs: a six-petalled flower, a jug and a libation-dish, each within a square frame. At first sight, the fourth side appears to be blank.

But closer inspection reveals faint traces of letters. This square frame once held the Latin inscription that gave details of the man who set up the altar, the god he dedicated it to, when and why. Unfortunately, since its discovery in the seventeenth century, the text has become illegible. But with a combination of modern technology and old-fashioned archival research, AshLI have produced a new reading.

Eagle-eyed Antiquarians

The altar was found intact in Foregate Street, Chester in 1653. By chance, the Chief Master of the Chester Free School, John Grenehalgh, happened to witness its discovery. Recognising its Roman origins, he returned the next day to transcribe its text, but was never confident about the accuracy of his transcription. The altar caused something of a sensation in antiquarian circles at the time, and several other transcriptions were made, each slightly different.

The inscription, already in poor condition when it was discovered, became increasingly worn after the altar was set up in a garden in Chester for some years. It was finally given to Oxford University in 1675 by Brasenose alumnus Sir Francis Cholmondeley, who came from a local landowning family from Vale Royal near Chester, and it became part of the Ashmolean collection. When Ernst Hübner examined the stone for CIL in 1873, he remarked ‘Vidi, sed vestigia tantum litterarum perpauca evanida dignoscere potui’ – ‘I have seen it, but I was only able to make out a very few, disappearing traces of the letters.’ He wasn’t able to read the text himself and had to rely on an earlier transcription by Randal Holme from 1688.

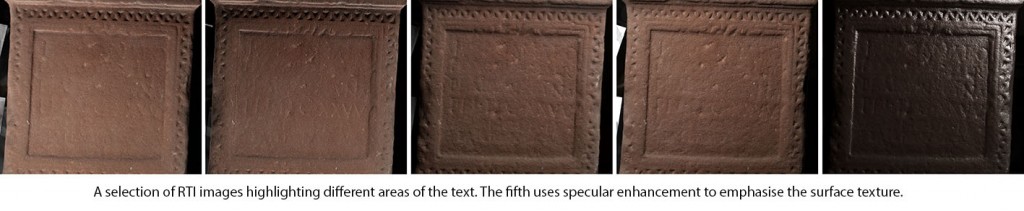

New Technology: RTI

Luckily, the AshLI team were able to use technology unavailable to earlier epigraphers. Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) uses a combination of photography and multiple light sources to map the surface of even very worn objects, bringing out marks that are invisible to the naked eye. Ben Altshuler from Oxford’s Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents was able to produce new surface images of the stone, which have confirmed the accuracy of much of Grenehagh’s initial report, but which also support a suggestion first made by Wilhelm Kubitschek in 1889, that the dedicator of the stone may have been a Spaniard from Clunia, a town in Hispania Tarraconensis.

New Reading

Unfortunately, even with the help of RTI, some areas of the text are still illegible: the surface of the stone has become too damaged. But by combining the old records, the RTI images, and knowledge of similar formulae, we now think the inscription reads:

I O M TANARO

T ELUPIUS GALER

PRAESENS CLUNIA

PRI LEG XX VV

COMMODO ET

LATERANO COS

V S L M

I(ovi) ° O(ptimo) M(aximo) Tanaro / T(itus) Elupius Galer(ia tribu) / Praesens [Cl]unia / pri(nceps) ° leg(ionis) ° XX V(aleriae) V(ictricis) / Commodo et / Laterano co(n)s(ulibus) / v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito)

‘To Jupiter Best and Greatest Tanarus, Titus Elupius Praesens, of the Galerian voting-tribe, from Clunia, princeps of the 20th Legion Valeria Victrix, in the consulship of Commodus and Lateranus, willingly and deservedly fulfilled his vow.’

A Cosmopolitan Cast

So this altar seems to have been dedicated by an officer of Spanish origin, in the Roman legion XX Valeria Victrix which was stationed during the Flavian period at Chester, near the border with Wales in the north-west of England. He was princeps of a legion, the second centurion in seniority, next in command after the primus pilus. The consuls he mentions give us a date of AD 154. The ‘Commodus’ here is Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus, now better known as the emperor Lucius Verus. His name ‘Elupius’ isn’t entirely certain, but now looks the most plausible among the many previous suggestions, which have included ‘Elypius’, ‘Elufruis’, ‘Flavius’, and even ‘Bruttius’.

But several mysteries remain: Tanarus is a Celtic thunder god, who appears in other inscriptions in the Rhineland and Dalmatia, but is otherwise unknown in Britain. Why are there no other British inscriptions to Tanarus, and why is a Spaniard dedicating an altar to a god more commonly associated with Germania?

A more detailed discussion of the stone, with full bibliographic references, will appear in the new catalogue of the Ashmolean Latin Inscriptions, which will be freely available online before 2016.

Sources Cited

Holme, R. (1688) The Academy of Armory (Chester)

Hübner, E.W.E. (1873) Inscriptiones Britanniae latinae (Berlin)

Kubitschek, J.W. (1889) Imperium Romanum Tributim Discriptum (Vindobonae)