It’s the year AD 2015. Happy New Year everyone!

For those of us who’ve grown up describing years as BC and AD, it can be hard to imagine doing it any other way. But describing a date as Before Christ or Anno Domini is based on a Christian tradition that began in the 6th century. So what did the Roman use before then?

Ab Urbe Condita

Romans living in 50 BC, for example, wouldn’t have thought of that year as being before anything in particular. Instead they had one of two choices when describing the year: the first was to give the date ab urbe condita, ‘from the founding of the City’. Rome, according to legend, had been founded in what we would call 753 BC, so 50 BC could have been described as DCCIII (703) ab urbe condita. But this kind of dating, linking back to a vague event, wasn’t particularly popular (except when it meant a party on big anniversaries).

Consuls and Calendars

Instead, most Romans preferred a more immediate system, one which suited their taste for honouring individuals: they described the year by saying which two men were consuls that year. The consulship was the highest elected position that a Roman man could achieve, and the top spot in the cursus honorum (the ideal career path for Roman politicians). The system was devised when Rome was a Republic, and the consuls were elected in pairs and changed annually to avoid either becoming too powerful. But, as time went on, the rules were gradually bent. When Rome became an Empire, and the Emperor was now the highest official, consuls lost much of their political power. Often the Emperor himself was one of the consuls, and effectively nominated the others, and some people held the position more than once.

This golden coin (aureus) was minted in AD 211-2, in the joint reign of the Emperors Caracalla and Geta. It shows the two brothers as consuls, sitting side-by-side in special “curule” chairs (a mark of office). This was not a good year for Geta. Click here to find out why.

But the names of the consuls were still used as a way of marking the year and, to avoid confusion, a Roman numeral was put after the names of those who had been consul before. So a consul’s name followed by III, for example, meant it was the third time they had held the position.

So, instead of 50 BC, a Roman would have said ‘the year that Lucius Aemilius Lepidus Paullus and Gaius Claudius Marcellus Minor were consuls’.

Sticky Dates

It was a method that had its pros and cons: the consuls took office on 1st January, and there was a new pair every year, so the names of the consuls gave a year its own individual identity. Everyone would have known who the two consuls were in that year, so in the short-term, it was easy to use.

On the other hand, it was a system which required people to remember who had been consuls in past years. Unlike BC/AD dating, which has a predictable order, the Roman system of consular dating didn’t follow any particular pattern. Someone in 2015, reading a plaque dedicated in 1995, could work out that it was set up 20 years ago. A Roman reading a plaque with the names of two consuls, would have to know when those men had been in office, to be able to do the same. Imagine having to describe a year by the Prime Minister in office at the time… and then imagine that there were two Prime Ministers… and that they changed every year.

Actually, it wouldn’t have been as bad as that. Most Romans, in their daily life would have described years in more personal ways (‘last year’, ‘four years ago’, ‘the year Marcus was born’), and reserved the consular dating system for more formal occasions, such as formal documents and inscriptions. And, of course, the state was keeping records, so there was no risk of forgetting the order in which the consuls held office.

DIY Dating

As is usual on inscriptions, the formula for giving the date was abbreviated to save space and effort. The year is described by giving the two men’s names, followed by the letters COS for consulibus, ‘while they were consuls’.

Why not try dating some Latin inscriptions for yourself? Below are three inscriptions from the Ashmolean collection which use consular dates. We’ve put the unabbreviated Latin and a translation beneath each one (so scroll gently if you don’t need help reading the inscription). To work out the equivalent BC/AD date, you can search for their names in this handy list.

The answers are at the bottom of the page. Good luck!

~O~O~O~O~O~O~O~O~O~O~

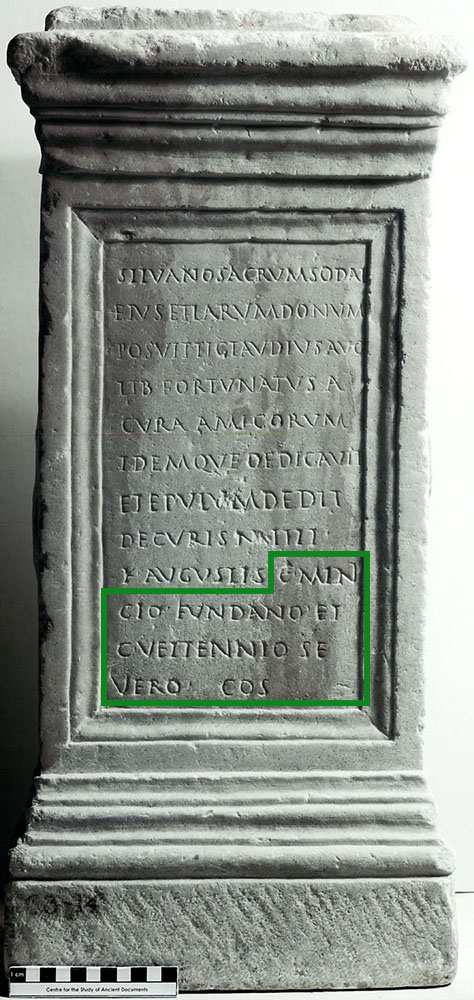

1. Easy: An altar set up by a freedman for the god Silvanus (Ashmolean ANChandler.3.14):

C(aio) Mini-

cio Fundano et

C(aio) Vettennio Se-

vero co(n)s(ulibus)

“When Gaius Minicius Fundatus and Gaius Vettennius Severus were consuls”

2. Tricky: on this brick stamp, the consuls’ names are written in the inner ring, and the word COS is in the centre (Ashmolean AN1972.1497):

Serviano III et Varo co(n)s(ulibus)

“When Servianus (for the third time) and Varus were consuls”

3. Fiendish: on this brick-stamp, we have only the end of the first consul’s name, and a very abbreviated version of the second consul’s name before the COS (Ashmolean AN1872.1500):

…Tit(iano et) M(arco) Squil(la) Ga(llicano) co(n)s(ulibus)

“When … Titianus and Marcus Squilla Gallicanus were consuls”

~O~O~O~O~O~O~O~O~O~O~

Answers:

1.The consulship of Gaius Minicius Fundatus and Gaius Vettennius Severus was in AD 108

2. The consulship of Lucius Julius Ursus Silvianus (for the third time) and of Titus Vibius Varus was in AD 134.

3. The consulship of Titus Atilius Titianus and Marcus Squilla Gallicanus was in AD 127.

A more detailed discussion of these objects, with full bibliographic references, will appear in the new catalogue of the Ashmolean Latin Inscriptions, which will be freely available online before 2016.

5 comments for “What year are we in? How did the Romans talk about years before BC/AD was invented?”