Of the four hundred inscriptions studied by the Ashmolean Latin Inscriptions team, none has proved more slippery than a little thanks-offering set up to Flora, the Roman goddess of fruit and flowers. AshLI has been following the trail of the inscription as it passed from collector to collector, leaving a trail of forgeries and confusion in its wake.

Last Seen

When Richard Chandler published his famous catalogue of antiquities in Oxford (his Marmora Oxoniensia), he began his description of the Latin inscriptions with an illustration of ten objects. The Flora plaque is shown on the far right, turned at a right-angle to the others. This is the last known record of the plaque in the Ashmolean collection. At some time after Chandler’s sighting in 1763, the little plaque disappeared, and its whereabouts still remain a mystery.

But while we can’t physically inspect the inscription today, we’re fortunate to have several sources that help us fill in the gaps. Not only do they give us important details like its findspot, size and material, but they also tell the extraordinary story of how the plaque came to England before mysteriously vanishing.

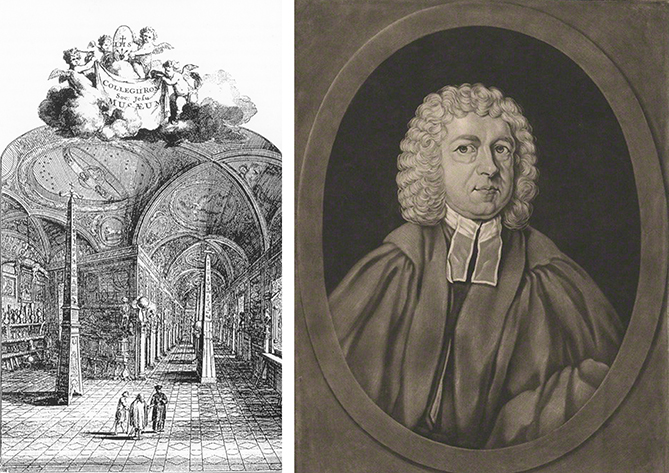

Opening plate of Richard Chandler’s Marmora Oxoniensia (1763), Volume 3, the last recorded sighting of the Ashmolean’s Flora plaque; the origin of the plaque – the Latium/Lazio region of Italy

Let’s start at the very beginning, a very good place to start…

The first, and most obvious, source of information about the plaque is the Latin text inscribed on the front. Thanks to Chandler’s drawing, we know it read:

FLORAE

TI(BERIUS) PLAUTIUS DROSUS

MAG(ISTER) II

V(OTUM) S(OLVIT) L(IBENS) M(ERITO)

‘To Flora.

Tiberius Plautius Drosus,

official for the second time,

fulfilled his vow willingly and deservedly.’

It tells us that the plaque was set up by a man named Drosus, a member of the senatorial Plautii family who came from Latium in Italy. From what we know about this family’s activities, and when they were politically active, we can tell that the plaque was originally set up in the first century AD.

This kind of dedication was a familiar part of Roman religion – gods and mortals kept in each other’s good books by exchanging favours for offerings (see our blog about a plaque to Hercules). Drosus proudly advertised that he had held a public office twice, probably as part of the district administration, or perhaps even a religious association, and it seems likely that this offering to Flora was to thank her for her part in his success.

A Collection of Collectors

Then the trail goes cold, and we have to travel forward 1600 years, to the writings of eighteenth-century historians to trace what happened next. In 1702, Raffaele Fabretti, recorded that the plaque had been discovered in a villa in Latium, and that it had been found ‘recently’. Although we’ve no way of testing whether these details are true, the Latium suggestion looks very credible: it was where Drosus and the Plautii family came from. But what does ‘recently’ mean?

It turns out that ‘recently’ probably meant ‘within the last fifty years or so’ (which doesn’t sound very recent, but is, admittedly, more recent than the first century AD). We know this because another eighteenth-century historian, John Ward, tells us that one of first owners of our Flora plaque was the extraordinary Queen Christina of Sweden. Famous at the time for what were considered ‘masculine’ traits, she was highly educated, read both Latin and Greek, and was a patron of the arts and sciences. Since Queen Christina died in 1689, the Flora plaque must have been discovered before then. We might even push the date of discovery back a little more: in 1654, Queen Christina abdicated her throne and moved from Sweden to Rome. It’s possible that this Flora plaque from Latium came to the Queen’s notice after she had moved to the region.

Three owners of the Flora plaque: Queen Christina of Sweden (1626 –1689); Decio Azzolini (1623 –1689); and Livio Odescalchi (1652 – 1713)

On her death, Queen Christina bequeathed part of her art and antiquities collection (including the Flora plaque) to her intimate friend, Cardinal Decio Azzolino. But he died only a few weeks after her, and his possessions passed to his nephew, Pompeo Azzolino. Uninterested in the collection and uncomfortable with speculation about the relationship between the Queen and his uncle, Pompeo sold most of it off. And so in 1692, the Flora plaque passed onto its fifth known owner, the Italian nobleman and Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, Livio Odescalchi. He was so proud to own an object once owned by Queen Christina, that he attached a small bronze label to the plaque which read EX REGIIS CHRISTINAE THESAVRIS – ‘From the Royal Treasury of Christina’.

Museum Hopping

But the Flora plaque didn’t stay still for long. By 1709, it was no longer in Odescalchi’s private collection, and the Jesuit scholar Filippo Bonanni saw it on display in the Kircher Museum in Rome. Only a few years later, in 1720, the Flora plaque was put up for sale in Rome, and bought by the English antiquarian, Richard Rawlinson, who brought it to England. One eighteenth-century source tells us that Rawlinson, like Livio Odescalchi, was particularly proud of the plaque precisely because of the little label that showed it once belonged to Queen Christina of Sweden. In 1753, Rawlinson gave his collection of inscriptions to the University of Oxford, where it eventually became part of the Ashmolean Museum. Here the story comes full circle, to Richard Chandler’s last definite sighting in 1763.

A Floridbunda of Floras: Friend or Faux?

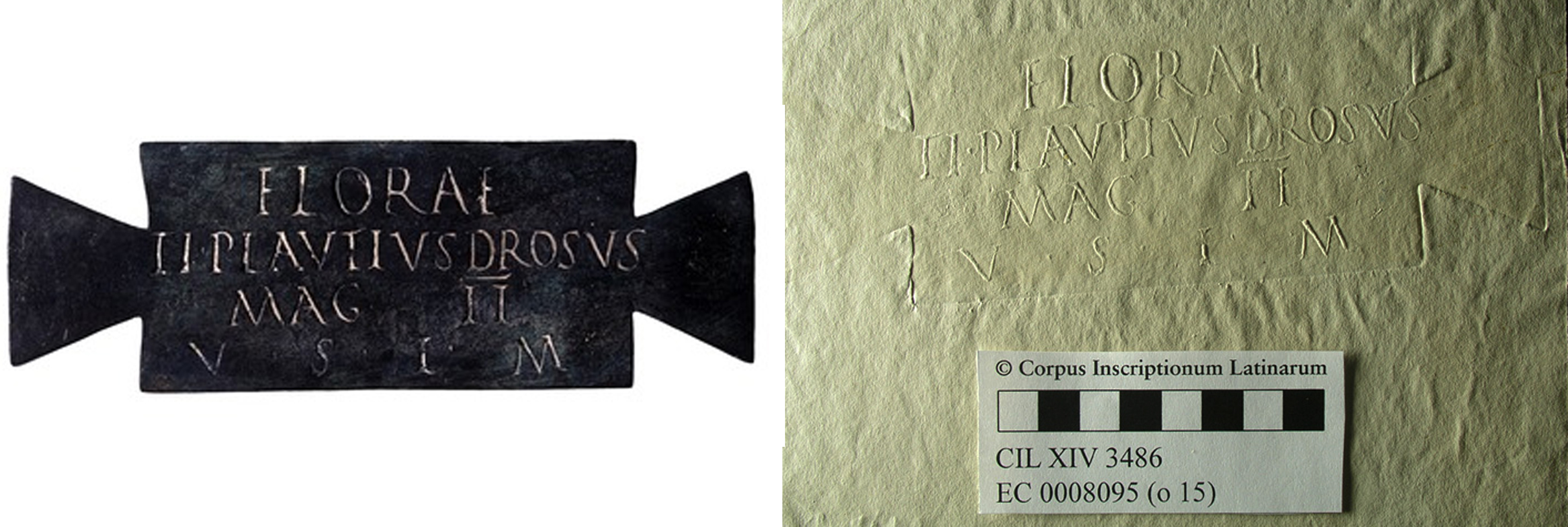

The eighteenth-century accounts helpfully tell us what was written on the plaque, where it was found and that it was made of bronze. But if we want to see what the missing plaque looked like, all is not lost because we know there are several other, identical versions in existence. In fact, there may be as many as six of them.

Three of the six are currently thought to be genuine: our missing, Ashmolean version; a version in the Naples Museum and a version in the Terme Museum in Rome. By comparing them, we can get an idea of the size of the plaque, which we can’t from Chandler’s drawing. From the Terme version, we know it was 6.6cm high, 19.5cm long, and 0.5cm thick.

The Terme version of the Flora plaque (inv. 65029), and a ‘squeeze’ (paper impression) of the Naples version (inv. 2570)

If these three identical plaques are genuine, we should imagine Drosus offering his thanks to Flora by setting up a series of plaques, perhaps in different Italian sanctuaries.

But we also know about three more versions of the plaque, and these are thought to be forgeries: in 1795, an Italian inscriptions specialist named Luigi Gaetano Marini recorded that he had seen a version of the Flora plaque being offered for sale by an antiques dealer, and condemned it as a modern forgery. Despite his identification, he was disappointed when the plaque still ended up in the Vatican Museum. We also know of another copy which was more honestly displayed by Scipione Maffei (1675-1755) in his museum in Verona, in a display dedicated to modern forgeries of ancient works. In a familiar turn of events, this fake version of the Flora plaque was found to be missing in 1872, and its current location if unknown. A third imitation of the plaque was spotted in the catalogue of the personal collection of Professor de Berger at Wittenberg University in Germany, which was published in 1754. Collecting antiquities, and even good replicas, was a popular hobby for educated gentlemen of the time, and the small, portable plaque to Flora, with its short text would have made it an ideal candidate for copying – whether the buyers knew what they were getting or not.

Finding Flora

All these different versions, and Flora’s habit of disappearing, have left AshLI with lots of difficult questions: Where is the Ashmolean’s copy of the plaque? Can we be sure it was genuine? Were the three versions identified as fakes, really fakes? Might some of the eighteenth-century accounts, which seem to be describing different plaques, actually be about the same plaque in different hands? And are there any more Flora plaques out there?

At the moment, we can’t answer these questions. As more museums and private collections create searchable catalogues and are more open about what they have, it becomes gradually easier to do this detective work, so perhaps, one day, the mystery will be solved. For the moment, we’re doing our bit with a new database of all 400 Latin inscriptions in the Ashmolean Museum collection, which will go live in 2016. But in the meantime, if you see Flora, will you drop us a line? And don’t let her out of your sight…

The bibliography behind our search will appear in the new catalogue of the Ashmolean Latin Inscriptions, which will be freely available online in 2016.

Image Sources:

- Wall-painting of Flora from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Flora_or_Spring_fresco_%28from_Stabiae%29#/media/File:Flora_mit_dem_F%C3%BCllhorn.jpeg

- Plate of Richard Chandler’s Marmora Oxonienia (1763), Volume 3: http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/arachne/index.php?view[layout]=buch_item&search[constraints][buch][alias]=Chandler1763&search[match]=exact

- Map of Latium/Lazio: « Lazio in Italy » by TUBS. Under licence CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lazio_in_Italy.svg#/media/File:Lazio_in_Italy.svg

- Portrait Queen Christina of Sweden, by David Beck: PD-KONST. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christina,_Queen_of_Sweden#/media/File:Drottning_Kristina_av_Sverige.jpg

- Portrait of Cardinal Decio Azzolini, by Jacob-Ferdinand Voet: https://www.lempertz.com/en/catalogues/lot/1027-1/52-jacob-ferdinand-voet-copy-after.html

- Portrait of Livio Odescalchi, by Jakob-Ferdinand Voet: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Livio_Odescalchi_%281655-1713%29,_by_Jakob-Ferdinand_Voet.jpg

- Engraving of the Kircher Museum: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kircher-Museum_im_Collegium_Romanum.jpg

- Portrait of Richard Rawlinson, by William Smith, after George Vertue: National Portrait Gallery, NPG D3996: http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portraitLarge/mw38255/Richard-Rawlinson

- Flora plaque in the Terme 65029: http://www.fotosar.it/index.php?it/57/catalogo/visualizza/1145

- Squeeze of Naples 2570: http://cil.bbaw.de/dateien/db.php?nummer=XIV+3486&andor=AND&nummer2=&fundort_antik=&fundort_modern=&provinz=#

1 comment for “Following Flora: AshLI on the trail of a little inscription that won’t stay put”