The Ashmolean Latin Inscriptions Project is very pleased to announce two pieces of good news: Firstly, we have a new member of staff: Dr Hannah Cornwell, recently returned from the British School at Rome, will join our joint Warwick-Oxford team…

Tag: Latin Inscriptions

A Roman Centurion in London

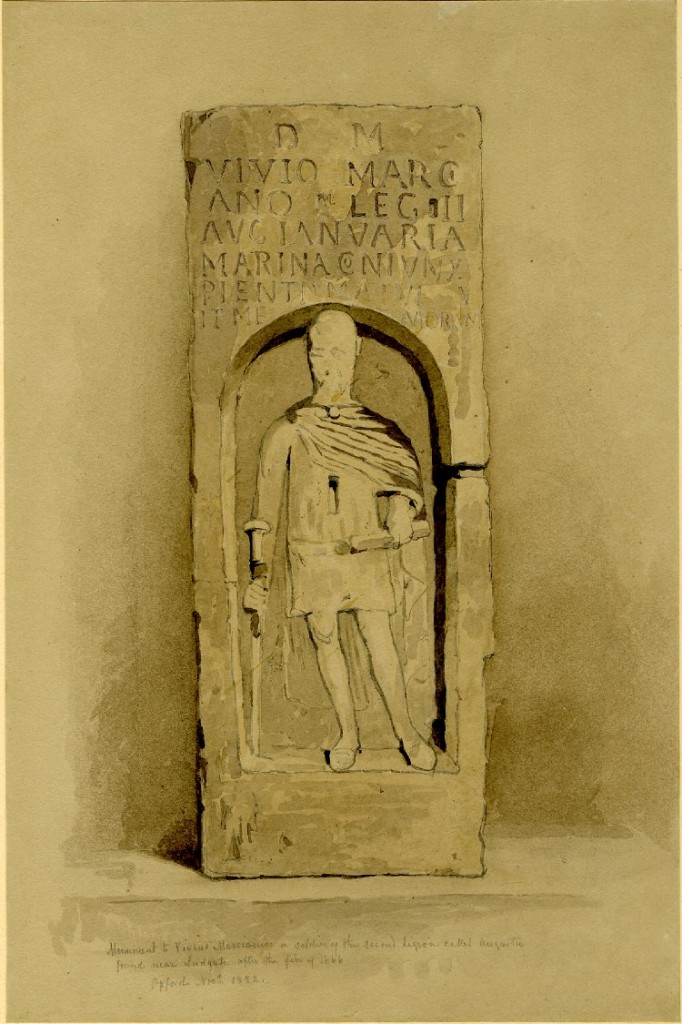

The many faces, and hairdos, of Vivius Marcianus

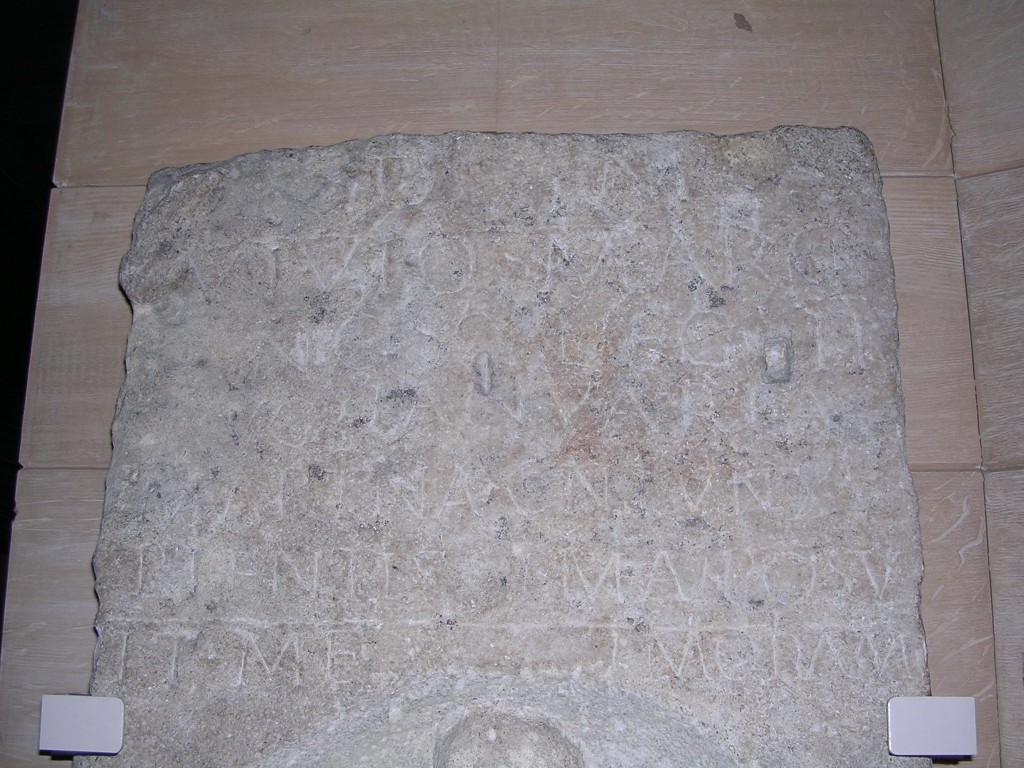

Ashmolean ANChandler3.10 (RIB 17), currently on display in the Museum of London. Dowel-holes in surface related to later reuse as building material. (H. 209cm, W. 78cm, D. 27cm). 3rd century AD.

In 1669, a limestone funerary relief was found by Sir Christopher Wren, when the church of St Martin’s in Ludgate Hill, London was being rebuilt following the Great Fire of London in 1666. With help from then-Archbishop of Canterbury, Gilbert Sheldon, the tombstone was brought to Oxford for display outside the new Sheldonian Theatre, and eventually became part of the Ashmolean collection. Today is can be seen on loan at the Museum of London.

The inscription tells us that it belonged to Vivius Marcianus, and was set up by his wife Ianuaria Martina.

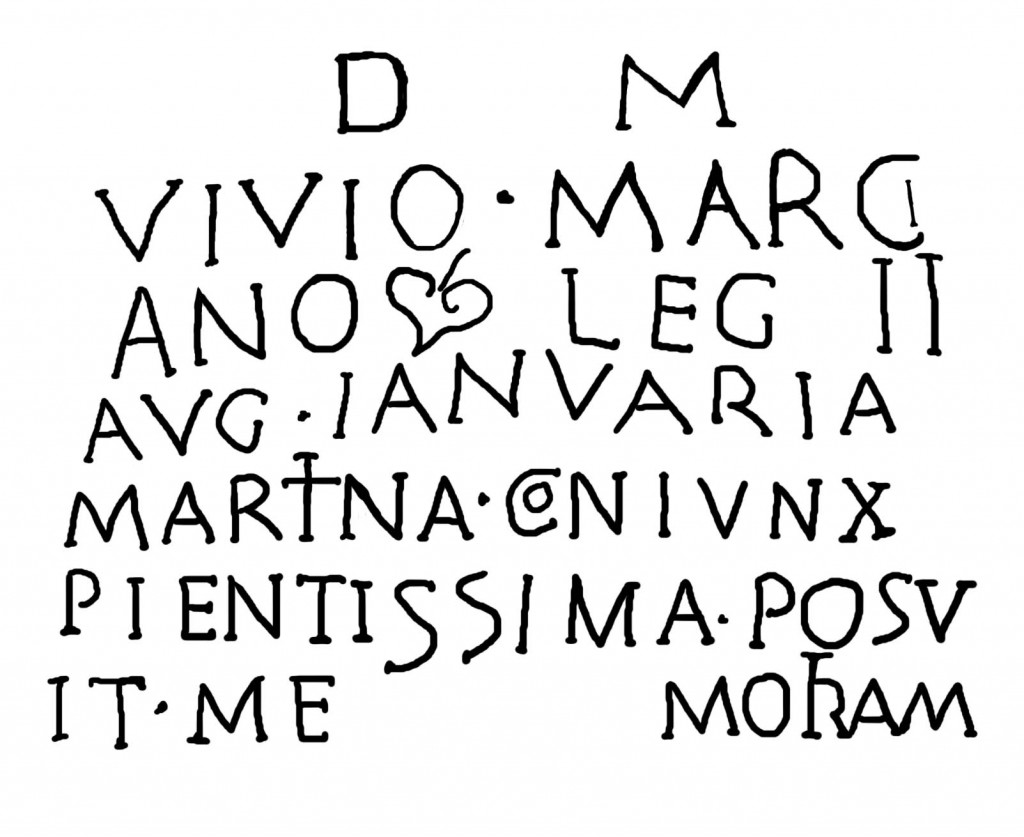

d(is) m(anibus) / Vivio ° Marci/ ano ° {ivy-leaf} leg(ionis)° II / Aug(ustae)° Ianuaria /5 Martina ° coniunx °/ pientissima °posu/it ° memoriam

‘To the spirits of the departed. Ianuaria Martina, most dutiful wife, set up the monument for Vivius Marcianus, of the 2nd Legion Augusta.’

In the words Marciano and coniunx, we see two examples of letters wrapped inside the C. In the words Martina and memoriam, we also find examples of ligatures, where two letters are stuck together: in the case of Martina, the ligature of the TI has led to many people to misread her name as Marina. The ivy-leaf in line 3 has also caused confusion and led some readers to insert extra letters or leave it out altogether.

The Many Faces of Vivius Marcianus

An image of Vivius Marcianus is shown at three-quarters life-size, standing inside an arched niche below the inscription. The surface of the relief is much worn, but we can see that he was shown wearing a short tunic, belt and cloak. In his left hand he holds what looks like a scroll, and his right hand holds a stick at this side. This confirms what the large size of the tombstone might have already suggested: that Vibius Marcianus was no ordinary soldier. The stick was the badge of office of a Roman centurion.

This interpretation of the damaged relief is based on what we, in 2014, know about the Roman Army and about Roman funerary art. But past studies of the relief haven’t always presented Vivius Marcianus in the same way. Here are just a few examples:

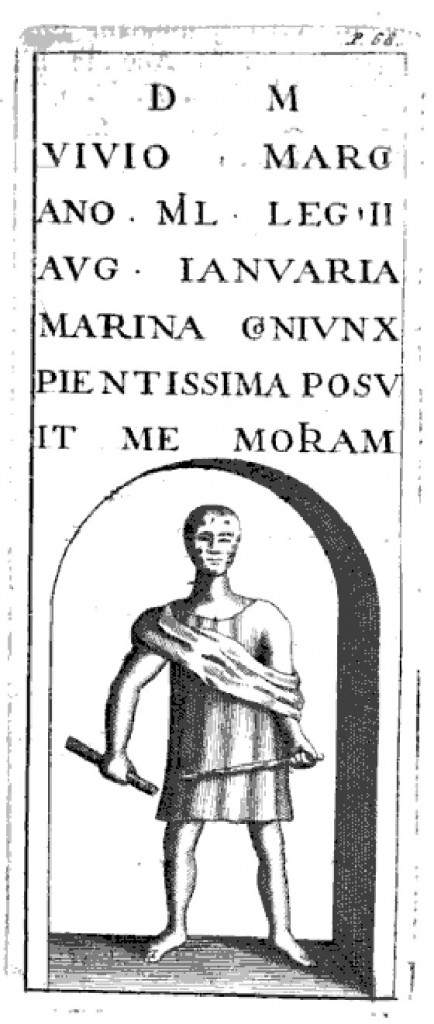

In 1676, Humphrey Prideaux imagined Vivius Marcianus with long hair and a fringe, and (rather dangerously) holding a long pointed sword by its blade. His reconstruction was clearly influenced by seventeenth-century fashions, giving him a contemporary hairstyle and replacing the stick with a long, thin blade unlike any Roman gladius.

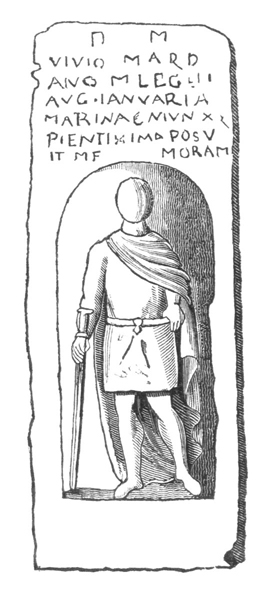

In 1709, Thomas Gale produced a very different reconstruction. This time Vivius Marcianus’ hair was short, and he was shown looking more poised and alert. But several details are missing and incorrect: the fall of the cloak behind, the belt, the scroll-like object in his left hand and the vertical stick in his right do not appear, suggesting he had not inspected the relief closely. In 1813, Thomas Pennant remarked how Vivius Marcianus had been ‘differently and faultily represented by Mr Gale.’

In 1827, Thomas Allen produced an illustration which restored the long cloak and belt, but showed the left hand empty. Rather than invent the hair and face, he chose to leave them blank. He offered a very impressionistic transcription of the Latin, with the words in line 5, Martina coniunx, almost unrecognisable.

In 1841, Charles Knight attempted his own version, drawing heavily on Prideaux’s early reconstruction, but now giving him a historical flavour with an old fashioned mop of curls. And the long sword has reappeared. The nineteenth-century readings of the relief are interesting because of the evident influence of contemporary ideas about Ancient Britain and Britons.

Many antiquarians had already tried to argue that Vivius Marcianus was a native Briton. Thomas Pennant, in 1790, even used the long hair that Prideaux had included in his reconstruction as proof that he was a soldier of the cohors Britanorum and that he was ‘dressed and armed in the manner of the country’. But in the nineteenth century, this interest in Marcianus’ Britishness had a slightly different flavour.

Charles Knight quoted the 1813 description by George Alexander Cooke which had Vivius Marcianus having ‘a plaid flung over his breast’ and holding ‘a sword of vast length, like the claymore of the later Highlanders’. The Victorian enthusiasm for Scotland and romantic historical themes appears to have influenced both men’s vision of our Roman soldier. Despite his flamboyant illustration, Knight admitted ‘in truth nearly all the points of his attire and accoutrements are so uncertainly delineated on the mutilated stone that anything like a complete or consistent picture of the whole can only be made out by an exercise of fancy’.

Before photography, these kinds of drawings, accompanied by verbal descriptions, were the only way to share information about ancient objects. But it was not always easy to tell how much of any drawing was based on fact and how much conjecture.

Considering how strong a temptation there was to make a damaged stone look more attractive in illustrations, the watercolour painted by James Wykeham Archer in 1852 is especially interesting. Archer’s is the only drawing to include the holes, breaks and areas of wear, suggesting a largely reliable record of the condition of the stone in the mid-nineteenth century. Importantly, it looks very much like it does now. Without Archer’s drawing, we might have believed that Allen, Knight and the others were able to see details that we no longer can, and perhaps trusted their illustrations more than we should.

Sources

- Allen, T. (1827) History and Antiquities of London, Westminster, Southwark and parts

adjacent, Vol. 1 (London) - Cooke, G.T. (1813) Topographical and Statistical Description of the Country of Middlesex (London)

- Gale, T. (1709) Antonini Iter Britanniarum (London)

- Knight, C. (1841) London vol.2 (Charles Knight & Co.: London)

- Pennant, T. (1790) Some Account Of London (London)

- Prideaux, H. (1676) Marmora Oxoniensia ex Arundellianis (Oxford)