As the feast of Saint Valentinus (a Roman, no less) is upon us, we’ve been thinking about love letters, or rather the different kinds of texts written by Romans about the people they loved. We know about the fiery passions of the Latin love poets, but what about the everyday Roman? What did a Roman husband write about his wife? A wife about her husband? Could we put the roman into romantic?

Here at the Ashmolean Latin Inscriptions Project, we decided to look at some of our Roman tombstones, to see what sort of things people had written about their loved ones. Although we found lots of terms of endearment, we quickly noticed that there was something funny going on…

Love: as easy as 1,2,3

It turns out that there’s not a lot of variety in these inscriptions. Just learn three, and you’re a Roman love expert:

1. carissimus/carissima – ‘dearest’. Just like the English word ‘dear’, the Latin word carus describes something of great value, whether financial or emotional (the –issimus/a ending means ‘most’ or ‘very’). In one of our 2014 blogs, we told the story of Annaia Ferusa, who set up a tombstone for a karissimus (with a Greek ‘k’) household slave, who had died at the age of 5 years, 2 months, 6 days, and 6 hours. While it’s true that she had to pay for his upbringing, we like to think she was calling the little boy ‘dearest’ rather than ‘very expensive’.

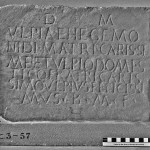

Carus and carissimus is one of the most versatile terms of endearment in Latin, an adjective suitable for all the family. In this short inscription, Ulpius Felicissimus uses the word twice – once for his mother and once for his brother.

d(is) m(anibus)

Ulpiae Hegemo-

nidi matri carissi-me

et Ulpio Domes-

tico fratri caris-

simo Ulpius Felicissi-

mus b(ene) m(erentibus) f(ecit)

‘To the spirits of the dead. Ulpius Felicissimus set this up for Ulpia Hegemonis, his dearest mother, and for Ulpius Domesticus, his dearest brother, who well deserved it.’

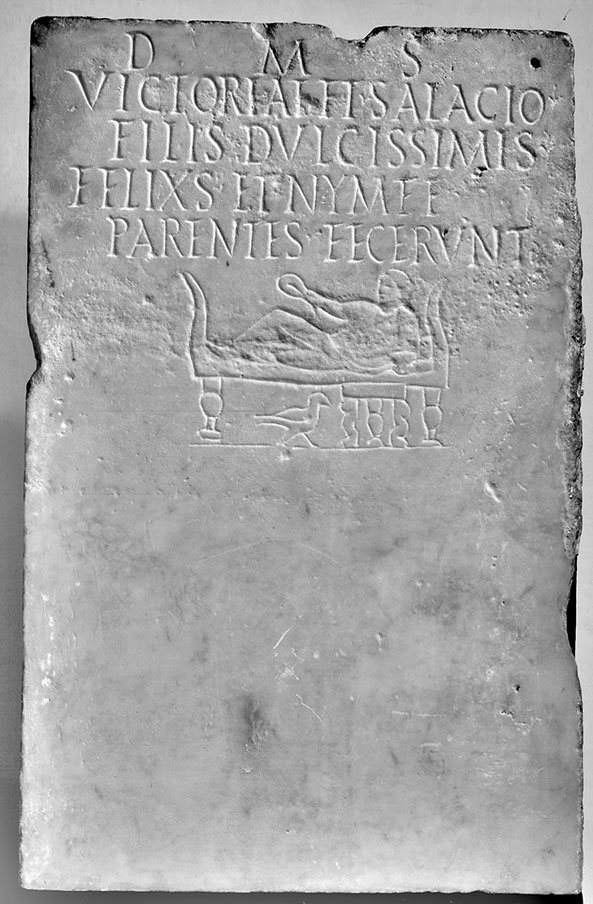

2. dulcissimus/dulcissima – ‘sweetest’. The Romans used the word dulcis in the exactly the same way we use ‘sweet’, both to mean ‘sugary’ and to describe a person. And, just as with ‘sweet’, it looks like it was a term that was a little bit too cutesy for grown-ups – we find it most often on the tombstones of children, like this one for a brother and sister (*sniff*).

Ashmolean ANChandler.3.35, 2nd/3rd century AD. The picture shows a man at dinner, holding out a celebratory wreath, probably intended to be a generic sign of ‘the good life’.

d(is) m(anibus) s(acrum)

Victoriae et Salacio

fili(i)s dulcissimis

Felixs et Nymfe

parentes fecerunt

‘Sacred to the departed spirits.

For Victoria and Salacius, their sweetest children, Felixs and Nymfe, their parents, set this up’

3. B M / bene merens – ‘well-deserving’ or ‘who well deserved it’. We’ll admit, this one sounds a bit odd in translation.

It didn’t mean that they deserved to die, but rather that they deserved to have a tombstone set up in their memory. Because they’re worth it. Most Romans had fairly traditional ideas about family duties, and bene merens was a quick and conventional way of saying that someone had led a good life, and done the kinds of things that were expected of them. The abbreviation B M is very common (see the tombstone set up by Ulpius Felicissimus in number 1, above), and is used to describe husbands, wives, children, parents and even freedmen. In fact, it’s so common that it doesn’t really tell us very much about individual relationships or personal qualities.

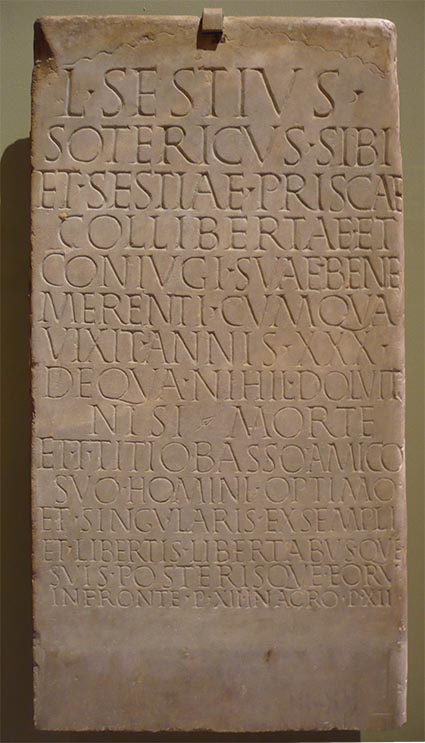

But one of our favourite Ashmolean inscriptions, hanging on the wall of the Randolph Gallery, gives us some idea as to what bene merens meant to one particular Roman husband. In this inscription, Lucius Sestius Sotericus marks his burial plot with a tombstone for his entire household. We learn that he met his wife, Prisca, when they were both slaves in the same household, and after 30 years together, he pays her a very Roman compliment: the only thing she ever did to pain him, was to die.

L(ucius) Sestius

Sotericus sibi

et Sestiae Priscae

collibertae et

coniugi suae bene

merenti cum qua

vixit annis XXX

de qua nihil doluit

nisi morte

et T(ito) Titio Basso amico

suo homini optimo

et singularis exsempli

et libertis libertabusque

suis posterisque eoru(m)

in fronte p(edes) XII in agro p(edes) XII

‘Lucius Sestius Sotericus for himself and for Sestia Prisca his fellow freedwoman and his well-deserving wife, with whom he lived for 30 years, and about whom he had no reason for sadness except through her death; and for Titus Titius Bassus his friend, an excellent man of remarkable conduct; and for his freedmen and freedwomen and for their descendants; 12 feet wide, 12 feet deep.’

Were the Romans unromantic?

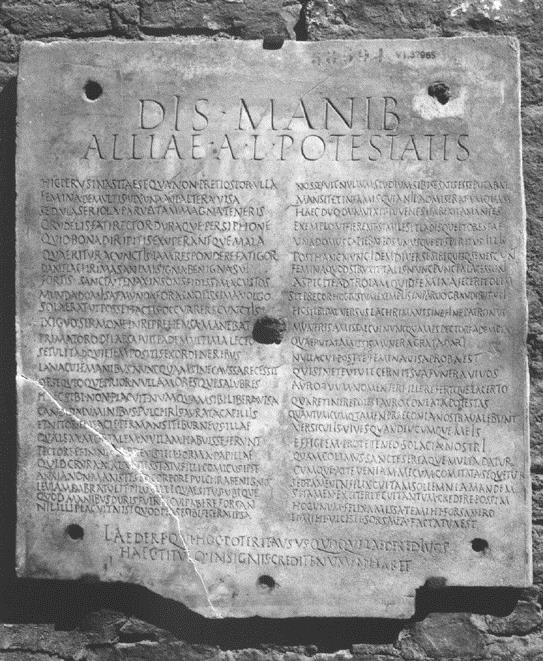

These conventional terms seem to suggest that the Romans were pretty restrained about their declarations of love. But this shouldn’t be taken as evidence that the Romans didn’t feel love or loss. Instead, it tells us more about what they chose to express on funerary monuments. Some inscriptions are more demonstrative – one amazing inscription in Rome describes a 3rd-4th century Roman woman called Allia Potestas who was apparently one third of a happy ménage à trois and, we’re told, was not only well-behaved but incredibly sexy (almost every part of her body gets a 5-star review from her two boyfriends. You can read a full English translation here, and find the Latin in CIL 6.37965). But for something as long-lasting, important and expensive as a tombstone, most Romans played it safe, choosing the traditional and dignified, over the passionate and personal.

Just to prove that this is more about the type of the text, than about the Romans being unromantic, we wanted to leave you with some snippets from a genre of text with very different emotional conventions:

Latin Poetry : love turned up to 11

Despite what 50 Shades of Grey may have done for the modern erotic novel, romantic and erotic poetry isn’t in fashion at the moment. But in ancient Rome, particularly in the 1st century BC, and 1st century AD, love poetry was a well-established literary genre, with its own familiar metres (like elegiac couplets) and characters (frustrated suitors, manipulative mistresses, stern doormen, etc.). Some of the most famous Roman poets wrote about love, in its many forms: from modest admiration and mutual adoration, to erotic fascination and bitter recrimination.

We asked some of our colleagues from Oxford’s Faculty of Classics to read us some of their favourite passages from these great poets in honour of Valentine’s Day, to show some of the sides of Roman love that don’t appear in our inscriptions. Here’s Professor Gregory Hutchinson, Dr Gail Trimble, Frà John Eidinow and Dr Rebecca Armstrong, reading from Propertius, Catullus, Horace, and Ovid. Hope you enjoy them.

Lots of love,

AshLI

xoxo

Click here to play (opens in new window).

1 comment for “Love Letters – How did the Romans write about the people they loved?”