A bilingual inscription from Delos. Ashmolean Museum ANMichaelis.209. (H. 0.84cm. Diam. 0.70cm)

Duty Free Delos

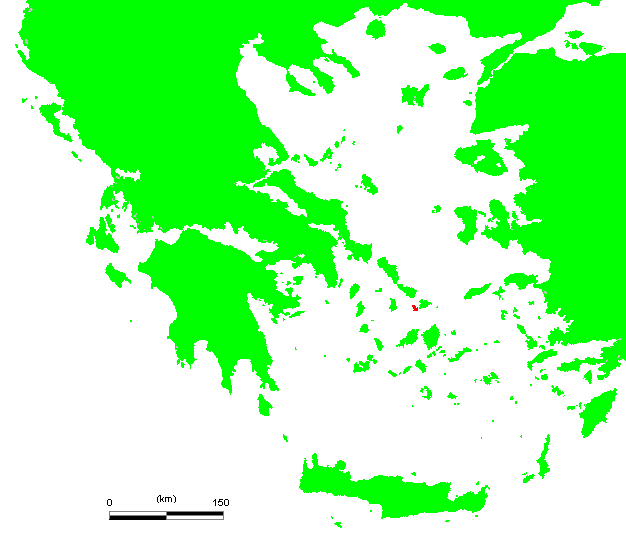

In the second century BC, the little Greek island of Delos in the Cyclades experienced an unexpected boom, as it became the place to do business in the eastern Mediterranean. Rome was not yet an empire, but Latin-speaking tradesmen were already very familiar the region. Everyone knew something about these enterprising people from Italy.

In 166 BC, the Romans made Delos a tax free port, making it an attractive place to trade goods and slaves. Many traders set up homes on the little island, making it a cosmopolitan commercial centre where Greek speakers and Latin speakers lived and worked side by side.

A Bilingual Inscription

(L) The Randolph Gallery at the Ashmolean Museum; (R) A colossal head of Apollo mounted on Avilius’ altar.

Today, the long Randolph Gallery of the Ashmolean Museum is lined with statues and reliefs from the Arundel Collection, and with a series of Greek altars which now serve as statue bases. These altars all follow a similar formula: a marble drum, shaped like a cotton reel, encircled with swags of foliage and bulls’ heads (bucrania, which refer to animal sacrifice). But one of these altars, now supporting a colossal head of Apollo, is an important record of relations between the Greek- and Latin-speaking inhabitants of Delos.

The altar dates to the late second century or early first century BC, when it was set up as a funeral marker for a man named Quintus Avilius. It is inscribed, in uneven letters, in both languages on the smooth surface of the drum: the Latin inscription at the top, the Greek at the bottom. But while what they say is largely similar, there are some revealing differences.

When a Roman is not a Roman

Q(uinte) Avili C(aii) f(ilie) Lanu(v)ine salve

‘Quintus Avilius, son of Gaius, of Lanuvium, farewell.’

The Latin inscription tells us that Quintus Avilius originally came from Lanuvium, a town in Latium, just over 30 km to the south-east of Rome. Someone from Lanuvium at this date (before the Social War) would not actually have been a Roman citizen. The Greek inscription, on the other hand, gives slightly different information:

ΚοΐντεἈυίλλιεΓαΐουυἱὲΡωμαῖε

χρηστὲχαῖρε

‘Quintus Avillius, son of Gaius, Roman, honest man, farewell.’

This inscription calls Avilius a Roman, even though he wasn’t. And our inscription is not the only Greek text from Delos to do this. It seems that traders from Italy who spoke Latin were routinely called Romaioi by the Greek speakers on the island, even though they weren’t from the city of Rome, or have Roman citizenship. As far as the Greek speakers were concerned, the distinction apparently didn’t matter. And, judging by Avilius’ altar, everyone, including the Latin-speakers, went along with it.

An honest Roman?

Another difference is the inclusion of the adjective χρηστὲ – ‘honest’ in the Greek inscription, which doesn’t appear in the Latin. We might wonder why it’s been added. Its meaning is complicated by the fact that inscriptions don’t include punctuation. If we take it with the preceding word, the phrase Ρωμαῖε χρηστὲ means ‘an honest Roman’, which isn’t very flattering to Romans! It might give us a clue as to how the Greek speakers of Delos felt about their Latin-speaking colleagues. But in fact, χρηστὲ belongs with the word which follows it. The final phrase χρηστὲ χαῖρε – ‘honest (man), farewell’, is really a common, stand-alone ending in funerary inscriptions from Delos, and the stonecutter put those two words on the line below to show they belonged to a new clause. In our English translation, at least, we can use commas.

If we want to find out about relations between the Greek and Latin speakers in Delos, perhaps most revealing of all is the fact that someone, perhaps even Avilius himself, made the decision to have his funerary monument inscribed in both languages. His friends, customers and clients could read about him in whichever language they preferred and see terms that they readily understood, even if those terms were not entirely accurate. It’s a thoughtful gesture, and perhaps no surprise from an island population that knew a thing or two about international marketing.