‘When Agrippina reviled him [the emperor Tiberius], he had her flogged by a centurion, causing her to lose an eye. When she resolved to starve herself to death, he had her forcibly fed, and when through pure determination she succeeded…

Author: AshLI

A Bullet with Your Name On – podcast 4

In 41/40 BC, the Romans were at war – with one another. At the town of Perusia, forces loyal to Mark Antony found themselves besieged by the troops of Octavian, the young man who went on to become the Emperor…

The Roman Intelligence Officer who was stationed in Britain – Podcast 3

The Roman Army wasn’t just legionaries and building roads… In our third podcast, we look at an unusual funerary inscription on display in the Ashmolean’s Randolph Gallery. It was set up for a speculator, an intelligence officer who was stationed…

(Re)visiting an old friend from Hadrian’s Wall – Podcast 2

Back in early September, AshLI challenged Twitter followers of @AshmoleanLatin to read a tiny bronze plaque in the Ashmolean Collection. By the end of the day, we were really getting somewhere: After some clever sleuthing from classics-lovers and amateur epigraphers,…

The Roman teenager who was his mum’s little superhero – Podcast 1

This month’s Latin inscriptions blog comes to you as a short podcast, recorded in the Ashmolean Museum’s beautiful Randolph Gallery. Hear AshLI’s Professor Alison Cooley and Dr Jane Masséglia talking about one of the team’s favourite objects. Listen to the…

Love Letters – How did the Romans write about the people they loved?

What year are we in? How did the Romans talk about years before BC/AD was invented?

It’s the year AD 2015. Happy New Year everyone! For those of us who’ve grown up describing years as BC and AD, it can be hard to imagine doing it any other way. But describing a date as Before Christ…

On the Feast of Saturnalia, my master gave to me…

A Roman Slave’s Carol As the shortest day of the year drew near, the Romans crossed their fingers for a kind winter and people from all walks of life made a break in their usual routine to honour the harvest…

Classics Teachers get special access to Ashmolean on “Teaching with Ancient Artefacts” Day

On 22nd November 2014, 38 teachers from around the UK came to Oxford for a one-day course on how to use ancient artefacts in their teaching. The day was organised by the Ashmolean Latin Inscription Project (AshLI), and delivered by…

Did the Romans believe in ghosts?

The haunted house…

It was a sprawling town house that anyone would have been proud to own. But every night, the sound of clanking chains and a terrifying vision of an old man, his shaggy hair crusted with filth, woke the inhabitants. With each visitation, their terror grew until, sick with sleeplessness, they abandoned the house. It was put up for sale, but no-one would go near it. Then, one day, a man arrived in town, a man famous for his rational mind. A man who didn’t believe in ghosts. Dr Llewelyn Morgan picks up the story with a recording he made especially for AshLI:

The story of Athenodoros and the haunted house comes from the turn of the second century AD, in a letter from Pliny the Younger to his friend Sura (Pliny, Letters VII.27).

Spookily familiar

The basic story – a place is haunted by a ghost who can find no peace until its bones are found and laid to rest – is a very familiar one (The Woman in Black, Coraline, and Sleepy Hollow all rely on it). It’s also very ancient. In Homer’s Odyssey XI, Odysseus meets the ghost of his comrade Elpenor in Hades, and discovers that he’s been left behind on Circe’s island. Elpenor had rolled off the roof where he was sleeping and broken his neck, and needs a proper burial.

The many faces of the Roman ghost

In modern, Western culture, ghosts are often associated with this kind of unfinished business. Set against the Christian tradition of heaven and an appealing afterlife, ghosts often need to have a good reason to be hanging around on earth when they could be somewhere better. But the Romans didn’t have just one idea about ghosts. Some, like the old man in Pliny’s story, were lemures, angry or overlooked spirits, who could cause trouble for the living. They were honoured annually with a series of feast days in May. Not surprisingly, lemures mostly appear in Latin literature (e.g. Ovid’s Fasti 5), since they tend to make good stories. Others ghosts were members of the natural, and ever-increasing band of dead ancestors and close relatives, who functioned as guiding and protective forces in Roman daily life. These spirits, the manes, were imagined as being in or under the earth, and were celebrated with a nine-day festival, the Parentalia, in February, and were often described as gods (di). The distinction between gods and protective spirits wasn’t one which the Romans would have worried too much about.

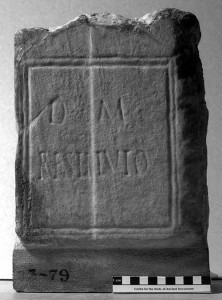

‘Dis Manibus’

It’s the assembled ranks of this second type of ghost, the ancestor-spirit, which are extremely common in Latin inscriptions. Roman tombstones often open with two letters: DM, short for dis manibus – ‘To the spirits of the departed’. It’s an address to those who have gone before which alerts them that another spirit is on its way, and is commended to their care. Even if the rest of the inscription is broken off, worn away, or downright horrible, the opening letters DM mean that we can be sure we’re dealing with a tombstone, and not some other type of inscription.

If we’re really lucky, the stonecutter might have included a slightly longer abbreviation, like the DIIS (this time with double ‘i’) MANIB we see on this ash-urn currently on display in the Ashmolean’s Rome gallery:

A toast for a ghost

One of the ways that the Romans kept the di manes happy was by making offerings. A recently deceased relative and the rest of the di manes could be honoured by pouring libations or leaving food on or near the grave. One of the pieces that the Ashmolean Latin Inscriptions Project hopes to put on display in 2015 is a remarkable tombstone for a woman named Livia Casta. In the middle of the stone is a relief carving of a Roman cup, pierced with four holes. The stone was originally set horizontally so that Livia Casta’s relatives could pour wine, honey and water offerings into the cup, which would drain through onto her ashes where she could enjoy it. Honouring the ghosts of dead relatives and the wider band of di manes was really a question of keeping them involved, and making sure they had their share of pleasures like food and drink.

Did the Romans believe in ghosts?

It’s always dangerous to make generalisations about what an entire culture believed. It’s tempting to use the evidence in literature and inscriptions to draw conclusions about what the Romans thought, but plenty of people read (and write) ghost stories without necessarily being convinced about the existence of ghosts, and plenty of people ask for things to be caved on tombstones because they’re traditional. Some Romans probably believed in ghosts, and some probably didn’t. But what’s very clear is that the Romans liked the idea of ghosts, and used them in various different ways: for managing luck, for keeping family memories alive and even, just like us, for telling scary stories.

A more detailed discussion of the Latin inscriptions shown here, with full bibliographic references, will appear in the new catalogue of the Ashmolean Latin Inscriptions, which will be freely available online before 2016.