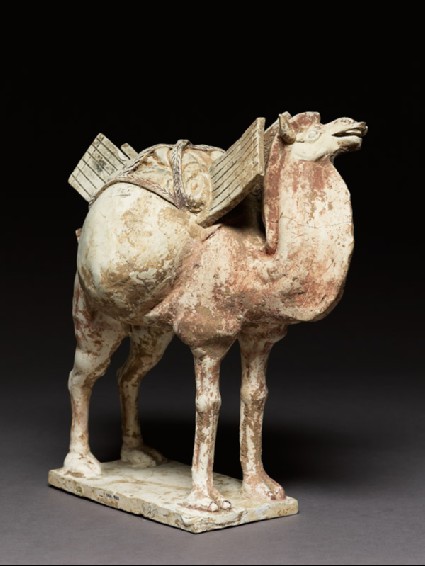

Model of a Camel, Tang Dynasty (AD 618-906)

Soft whiteware, remains of paint

by Izzy Galwey

As many historians have commented, the Tang dynasty was extraordinarily cosmopolitain era of Chinese history. Trade routes stretched away across Asia in all directions; the capital city, Kaifeng, was a bustling metropolis with citizens hailing from Persia to Indonesia. The Tang dynasty was a vast driving power behind economic networks which stretched across Eurasia.

Another notable characteristic of the Tang in comparison to many later dynasties is its focus on the North-West. Over the centuries, Chinese imperial culture followed migration patterns and shifted steadily south – to some extent, the Tang bucked this trend. Goods and ideas from Central Asia and beyond were firmly in fashion. Buddhism, polo, Tibetan wool, Sogdian whirling dances – and, of course, camels.

These beasts of burden, perfect for overland trade, would have been a relatively common sight on roads across the empire, particularly in the northern frontier areas. It’s no wonder, then, that many people elected to have sculptures of camels like this one buried with them – it’s a nod to the fact that these animals were indispensable, and an important part of everyday life.

I’ve never actually ridden a camel, much less tried to lead one across hundreds of miles of mountain and desert, but this expressive sculpture still strikes a chord with me. For a Tang dynasty civilian seeing this sculpture, I imagine their first reaction would be a double-take — it’s a tomb sculpture, after all, quite spooky! – but after that, I think they would be struck, as we are, by the skilled craftsmanship and the expressiveness of this sculpture. The camel is laden with several heavy-looking packages, forming a textural mass almost as big as the animal itself. She is standing tall and arching her head backwards, looking slightly affronted – but not particularly surprised – at the huge load which has been placed on her back. I imagine that she is a seasoned voyager who has been in the trade for some years – still in her prime, and a valuable asset to her owner. Indeed, when I look at this camel – and other Tang sculpture, from horses to Buddhas to women playing polo – it is hard not to bring it to life in my mind.

Tang dynasty sculpture is notable for this expressiveness. With the spread of Buddhism from South and Central Asia, art styles from as far afield as modern-day Pakistan found their way into China for the first time. Travelling with monks, hired workers – and, on a less savoury note, conscripted or captive craftsmen – these motifs and techniques were enthusiastically adopted and modified by Chinese artisans. They lend sculpture of this period a flamboyance and expressiveness which caused Tang poets to compose verses in praise of the work they saw at court and elsewhere. For centuries, Tang sculptures have been highly valuable collectors’ items, in China and abroad.

For me, this sculpture enlivened the exhibition space in which it was situated. It looked like a statue that was going places; and, being a camel eager to get home, it stubbornly dragged me a little way along with it. It became a tiny window into the bustling, cosmopolitan world of the Tang; although it was probably created to be part of a burial, for me it could hardly have been more alive.

EA1956.988

Earthenware figure of a camel from China Tang Dynasty (AD 618-906) Currently on display in Gallery 28 Presented by Sir Herbert Ingram, 1956. Accession no.EA1956.988