by Isabella Cullen

Walking around the Islamic Middle East department, gleaming lacquerware immediately draws the eye. Particularly elaborate is one painted surgical kit, dating from c.1820-40, which probably originates from Isfahan, Iran. The artefact is illuminated by its reddish-brown varnished cover, created with the papier-mache technique typical of Islamic lacquerware. Unlike the European method of applying lacquer to wood, Islamic artists typically pasted together sheets of paper to form a thick smooth surface, which was then painted in watercolour before the layer of varnish was applied.

Lacquerware was hugely popular in Iran towards the end of the Safavid Dynasty (1501-1722) and into the period of Qajar rule (1785-1925). The rule of Fath ‘Ali Shah saw a fondness in the royal court for this lacquering technique, used in artwork from the period which drew from the iconography of the last imperial dynasty in Persia – the Sassanid dynasty (224 – 651). Fath ‘Ali commissioned lacquerware pieces to establish his reign, hanging multiple lacquered portraits of himself in his royal estates and sending them as diplomatic offerings to kings overseas. The rule of his successor Muhammad Shah saw an even more concerted shift towards small lacquer paintings of the monarch to commemorate his royal authority.

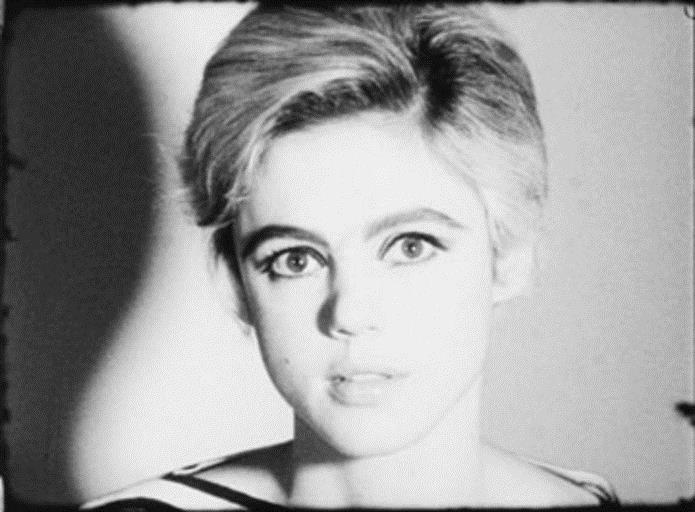

This surgeon’s kit contains two drawers full of tools of extraordinary shapes, mostly made of steel, though some are of bone or mother-of-pearl and others inlaid with gold. Painted on the cover, framed by a delicate floral border, are the Holy Family along with accompanying figures. Though art of the Safavid period most commonly depicted nature and intricate patterns, this Islamic illustration of human figures and Christian iconography is not particularly unusual. The 1800s saw the conspicuous influence on Islamic artists of Christian European art entering Iran, with images of St Peter and the Holy Family, for instance, found among surviving artworks. This shift was often marked by portraits with attention to perspective and shading, rather than geometric shapes, as well as by biblical subject matter. The cross-cultural interaction was even represented in the dress and artistic representation of Muhammad Shah: the ruler introduced weapons from Europe into the Iranian arsenal and came to be depicted in European-style dress, with a military frock coat and blue sash coupled with his royal jewels and the Asian fleece ‘astrakhan’ cap.

The European influence on its subject matter links this surgeon’s kit to Isfahani painter Najaf ‘Ali. A prominent artist, active from around 1815-85, his artworks often depicted the Holy Family and could have included this delicate piece. Najaf ‘Ali’s handiwork would account for the European-style figures in this image, with Mary wearing the blue material characteristic of her representation in Renaissance art. She holds on her lap the baby Jesus, clad in swaddling cloth and the scene is dominated by the swathes of red fabric in which the surrounding figures are wrapped. The women’s hair is elaborately tied, their faces round and big-eyed in a style inherited from the art of the Zand dynasty (1750-94).

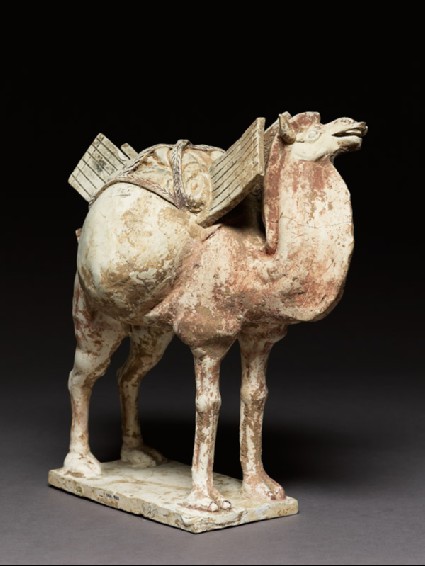

The illustration on the surgeon’s kit seems consistent with confirmed artworks by Najaf ‘Ali, such as this lacquer qalamdan (pen box) pictured, signed by the creator during the Qajar period at around 1855-56. Its central panel shows a Christian saint clothed in black, surrounded by depictions of the Khaju Bridge and the Ali Qapu Palace in Isfahan and patterned with floral motifs. The landscapes pictured possibly allude to the tale of the shaikh San’an and the maiden, a story from Attar’s Conference of the Birds. According to legend, San’an journeyed to Greece where he fell in love with a Christian maiden. Having converted to Christianity at her instigation, he burned the Quran and tended to the pigs, in rejection of his former faith. Eventually he returned to Islamic practice after the desperate prayers of his followers and having felt the true love of god. This formed the subject for many Iranian art pieces at the time, yet here is combined with the image of a Christian figure in a combination of European and Islamic influences which can be observed also in the beautiful surgeon’s kit.

For more information on the Surgeon’s Kit see http://jameelcentre.ashmolean.org/object/EA1955.1.2