BY ABBEY ELLIS

Forget match.com and OkCupid, the Ashmolean Museum has all the romance you need this February 14th. The following selection of objects from the museum’s displays, as well as a few gems from the vaults, will give you a taster of what you can expect on a Valentine’s visit.

1) Meet the goddess of love!

On this lekythos (an ancient Greek perfume vessel), Aphrodite, the goddess of love, is depicted riding a swan. The swan was a potent symbol of love in ancient Greece; as well as being associated with Aphrodite, the amorous god Zeus turned himself into a swan in order to get close to one of his many mistresses, Leda, without his wife finding out!

Object not currently on display, find out more here

Attic red-figure lekythos with image of Aphrodite riding a swan,

from Tomb 57 at Arsinoe (Marion)

donated by Cyprus Exploration Fund (AN1891.451

2) A wedding day to forget…

On a tiny gold iconographic ring, Saint George, the patron saint of England, is shown with the famous dragon, and the figure of a princess, dressed as a bride. According to legend, the princess in her bridal gown was to be fed to the plague-bearing dragon that was terrorizing her kingdom. But Saint George slew the dragon and rescued the princess before her wedding day ended in disaster.

Item not currently on display, see the ring for yourself here

3) Roman-ce in the Randolf Gallery

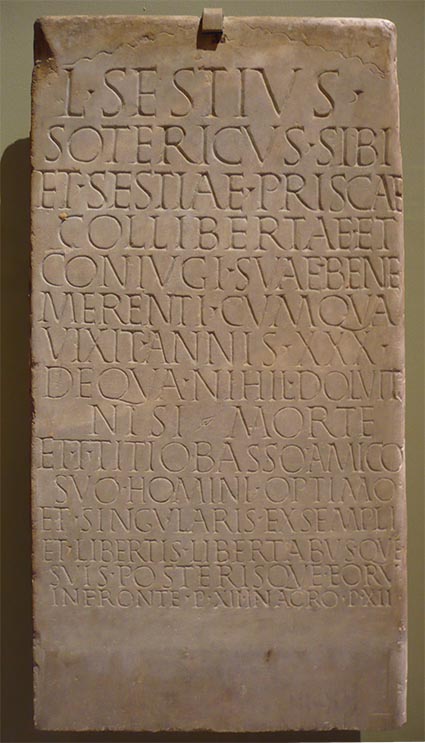

Head to the Randolf Gallery for a spot of romance from the 1st / 2nd century AD. On his tombstone, Lucius Sestius Sotericus, a Roman ex-slave, commemorates his “well-deserving wife / coniugi suae bene merenti”, Sestia Prisca. The tombstone reveals that the only thing Sestia did to hurt her husband was to die! This may not be the most romantic statement by modern standards, but for a Roman woman, this was as high a compliment as any.

4) A Kabuki Love Triangle

Woodblock prints were massively popular in 19th and 20th century Japan; they commonly represented actors from kabuki plays, dressed in their theatrical costumes. In this tripartite woodcut, actors are shown performing the story of geisha Kasaya Sankatsu. Two merchants are depicted on opposing panels, competing for her love. Sankatsu, shown in the central panel, extends a red sake cup toward each man, emphasizing her divided loyalties. Both men draw their swords in anticipation of a fight.

Item not currently on display, read more about it here

Here two merchants compete for the love of the geisha Sankatsu. Sankatsu holds the two halves of a red sake cup in her hands, demonstrating her divided loyalties towards the two men.

Date 1849 – 1850

5) When is three not a crowd?

Part of Flemish artist Jacques de l’Ange’s Seven Deadly Sins series, this oil painting is named ‘A Loving Couple’, who represent the vice of Lust. A young woman sits centrally, holding a candle, wrapped in the embrace of the ardent male figure sitting beside her. Also illuminated by the candlelight is another male figure, gazing out at the viewer with a knowing look. His bare shoulder suggests that something untoward is about to happen…

Not currently on display, more information can be found here

attributed to Jacques de l’Ange (documented 1631-2 – 1642)

A23; oil on copper; 36 x 28 cm

WA1845.23

A Loving Couple: ‘Lust’

If you would like to see any of the objects which are not currently on display at the Museum, please contact Sarah at public.engagement@ashmus.ox.ac.uk about the possibility of arranging a viewing.